I have been reading a lot about Rupert Brooke lately, in connection with a couple of personal projects of which, hopefully, more later. There are a fair few works on Brooke but the vast majority suffer from an obvious problem - length. Brooke was astonishingly busy, he wrote a lot from an early age, he had an enormous social circle and he travelled the world. But even so, he was only 27 when he died, and you simply can't justify 500+ pages for a life that short.

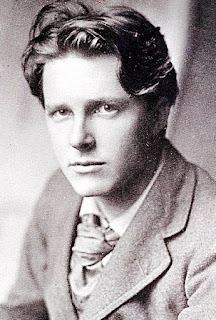

John Lehmann (1907-87) came of an astonishingly intellectual and creative family. His sister Rosamund was a novelist, his sister Beatrix a highly-celebrated actress. John was a poet and publisher. He founded New Writing in 1936, became a managing director of the Hogarth Press in 1938 and founded his own firm, John Lehmann Limited, in 1946. Finally, in 1954, he started The London Magazine. It's all very close-knit, a bit incestuous, and a bit artsy-craftsy. Which made him the perfect author for a critical biography of Rupert Brooke, who was a beneficiary and part-creator of similar arrangements before his ludicrous death in 1915. Best of all, Lehmann can do in 170 pages what Brooke's other biographers can't manage in several hundred pages. He brings Brooke alive in all his contradictory aspects - obsessed with women but offensively dismissive when the mood takes him; flirting with homosexuality but keeping his patron Eddie Marsh, who worshiped him, at a very resolute arm's length; globetrotting but always trying to micromanage his English friends. He was not a nice man but he was extraordinarily beautiful. He was a talented poet, more gifted than most in his day but did not live long enough to become truly great. And, as Lehmann says, he has been abandoned by the lirerary world which prostrated itself before his metaphorical shrine in 1915, in favour of those who came shortly after him and who lived long enough to experience the true horror of mechanized war: Sassoon, Owen and Graves.

Lehmann treats Brooke's service in a respectful and fair manner. Brooke was a volunteer, as everyone was in 1914. He did not ask Marsh, who was Churchill's secretary, to get him a safe billet in the Royal Navy Voluntary Reserve and it soon proved not to be particularly safe. Lehmann is better than most is describing Brooke's single experience of being under fire, in the long-forgotten farce of the British attempt to relieve the German siege of Antwerp. And let us not forget that Brooke was en route for the Dardanelles and the mass slaughter of Gallipoli when sunstroke did for him.

For anyone wanting to dip their toe into Brooke studies and come away with solid facts and a sound appraisal of his achievements, I cannot recommend Lehmann too highly.

No comments:

Post a Comment