Total Pageviews

Thursday, 31 December 2015

The Wolves of London - Mark Morris

I had not come across Mark Morris before spotting this, the first part of his Obsidian Heart trilogy, in my local library. I am already on the lookout for more.

Wolves is a horror/fantasy adventure with the added bonus (so often missed) of an engaging protagonist, Alex Locke, goalbird turned psychology lecturer, with something worthwhile at risk - he wanders from the straight and narrow because his eldest daughter's boyfriend is in bother, and gets stuck there when his younger daughter is kidnapped. The writing style is lively but nowhere near so lively as Morris's imagination. The surprises and twists keep on coming and kept me entertained to the very end.

Being a trilogy, the end is not conclusive and I admit I would have preferred some loose ends to be resolved. I expect I shall just have to pick up Book Two, The Society of Blood, to satisfy my curiosity,

By the way, the artwork on the cover, by Amazing15.com, is just superb.

Saturday, 26 December 2015

1Q84 Book Three - Haruki Murakami

OK, not the best idea to read book three of a magnum opus with no knowledge of the first two. But there we are. This is what I did - and it didn't matter. Murakami's dystopian world is so similar to the 'real' world as it was in Japan in 1984 that it makes no difference. His big concept is self-explanatory and does not subsume the three main characters, Aomame, Tengo and Ushikawa, Aomame has crossed into this world and killed the Leader of the Sakigake sect. She is being hidden by the Dowager but it obsessed with finding Tengo, briefly a schoolmate twenty years ago. Tengo is a part-time teacher who has ghost-written the sensational bestseller Air Chrysalis for the teenaged prodigy Fuka-Eri, real name Eriko Fukada. Air Chrysalis is ostensibly science fiction but actually it is an expose of the Sakigake cult. In this world - which no one has noticed is different, even though the main difference is two moons - the air chrysalis and the Little People who make them are real. Ushikawa is the profoundly ugly investigator who has been hired by Sakigake to track down Aomame. He goes to great lengths because he feels responsible, as he was the one who vetted her when she started work for the cult. Unable to breach the Dowager's elaborate security he decides to track down Tengo instead.

It is an intriguing book, which keeps rumbling on in the mind long after you've put it down. The Little People, when they appear, are jaw-dropping. Who is the unseen fee-collector for the national TV service who keeps banging on people's doors - even when they haven't got TVs? What is his relationship to Tengo's comatose father? What difference does the smaller, greenish moon make and why has nobody noticed?

Murakami's cool, understated prose makes the bizarre instantly acceptable - and, when the truly bizarre things happen, gives them double the impact. By focusing on the three main viewpoint characters, and giving them each a chapter in turn, he builds an appreciation of their personalities by sheer accumulation. Their linking characteristic is a patient stoicism - it doesn't matter how long Ushikawa has to stake out Tengo's apartment; Aomame cannot and will not leave Tokyo for a safer location until she has found Tengo, even though she has no reason to believe he has thought about her since they were ten years old; and Tengo is content to sit by the bedside of the father for whom he has no feelings whatsoever, using his spare time to plod away at his novel.

Superb. I will be happy to read the other two books (published in a single volume in the UK) but what really appeals to me is Murakami's earlier international successes, Norwegian Wood and Kafka on the Shore.

Friday, 18 December 2015

Beatrice and Her Son - Arthur Schnitzler

Schnitzler was the Viennese novelist of the Freudian era. Beatrice and Her Son is one of his mature works, published just a year before World War One. It is is very short (three chapters and less than 100 pages) but very dense and ultimately quite shocking. Beatrice is the widow of a celebrated actor. She is probably not yet forty (Schnitzler is far too subtle to specify) and reasonably well off. Some respectable but slightly dull men of around her own age are showing an interest, now that her mourning period can be considered to be decently done. But on her summer holiday in the mountains with her son Hugo it is one of Hugo's schoolfriends that she takes to her bed. Schnitzler is a psychological novelist and sets up many reasons for her scandalous behaviour, Is it boredom, novelty, risk - or simply revenge? Revenge because the young man Fritz has hinted that Beatrice's late husband (of whom he does a good impression) had affairs - and/or revenge because Hugo is sleeping with an older woman, a former actress who may or may not have been one of his father's mistresses. Beatrice only regrets her amour when she overhears the boys talking? Are they talking - sniggering - about her? That same night Hugo comes home dejected. Beatrice guesses that his lover has dispensed with his services. How can she recover what she and Hugo had before the summer? The innocent intimacy of mother and son...

This is depth that Schnitzler is able to cram into his novella. He switches between profound internal monologue and meaningless social chit-chat. He probes Beatrice's character and motivations so deeply that a single paragraph lasts ten pages. Yet he never bores, probably because he keeps the novella so short, and he never lectures us with his ideas. Crucially, he does not judge his character. He merely gives us the symptoms and leaves us to make our own diagnosis.

This book is superb - the novella, which I love, at its best. I shall definitely be reading more Schnitzler.

Wednesday, 16 December 2015

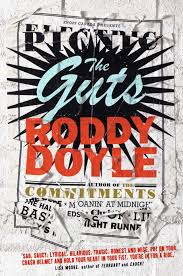

The Guts - Roddy Doyle

The Guts (awful title) is Roddy Doyle's return to Barrytown and Jimmy Rabbitte, quondam manager of the Commitments.

Jimmy is middleaged now but still in the music business, having sold his nostalgia website just before the Irish Tiger was shot dead in the Crash of 2008. Jimmy and Aoife retain an interest in the business, though, because it is their passion. At the start of the novel Jimmy is diagnosed with early stage bowel cancer, hence the horrible title. Doyle, however, neither dwells nor delivers on the premise. Jimmy seems to sail through his gruelling treatment, hence we do not get the full impact of his 're-birth' as he rediscovers the cutting edge of proto-punk Irish folk music from the early Republic and, this being a very effective comedy, composes and records the key song he just can't find for the album.

Just as Jimmy rediscovers his musical soul, so he reunites with his long-lost brother Les. Again, a promising storyline which Doyle fails to deliver on. When Les visits Ireland and joins Jimmy at the festival where the fake song (which has, of course, become a YouTube sensation with the young) has to be performed, there is no surprise, no revelation.

The Guts came out in 2013 and completely passed me by. I fancy it didn't get much publicity because of the shortcomings outlined above. Nonetheless Doyle is one of the top Irish novelists of a pretty good generation. No one says so much with monosyllabic dialogue. The Guts might be technically flawed but it is nevertheless a joyous, hilarious, life-affirming read.

Jimmy is middleaged now but still in the music business, having sold his nostalgia website just before the Irish Tiger was shot dead in the Crash of 2008. Jimmy and Aoife retain an interest in the business, though, because it is their passion. At the start of the novel Jimmy is diagnosed with early stage bowel cancer, hence the horrible title. Doyle, however, neither dwells nor delivers on the premise. Jimmy seems to sail through his gruelling treatment, hence we do not get the full impact of his 're-birth' as he rediscovers the cutting edge of proto-punk Irish folk music from the early Republic and, this being a very effective comedy, composes and records the key song he just can't find for the album.

Just as Jimmy rediscovers his musical soul, so he reunites with his long-lost brother Les. Again, a promising storyline which Doyle fails to deliver on. When Les visits Ireland and joins Jimmy at the festival where the fake song (which has, of course, become a YouTube sensation with the young) has to be performed, there is no surprise, no revelation.

The Guts came out in 2013 and completely passed me by. I fancy it didn't get much publicity because of the shortcomings outlined above. Nonetheless Doyle is one of the top Irish novelists of a pretty good generation. No one says so much with monosyllabic dialogue. The Guts might be technically flawed but it is nevertheless a joyous, hilarious, life-affirming read.

Wednesday, 9 December 2015

Transition - Iain Banks

The problem with sci fi is that there is a balance needs to be struck between big idea and human interest. So far as I am concerned Arthur C Clarke never found it, albeit his ideas were admittedly huge. Transition isn't officially sci fi, in that Banks hasn't used his middle initial, his usual sci fi signature. Perhaps he considered it more of a dystopian novel. If so it is a multiverse dystopia. His polished narrative skills just about got me through the 450 pages, and there were many passages of great interest, but there was no human interest, absolutely none, and that was a huge disappointment.

The crux of the matter is there are too many central characters spread across too many parallel Earths, none of them emotionally engaged with any other. None have any engaging human traits and all are, to a greater or lesser extent, servants of the all-powerful Concern - the ubiquitous future-Nazis of far too many similar works. Their means of travel - the titular transition - is trite, a device for getting them out of any peril at the speed of thought. The consequences of the device are blithely ignored by Banks whereas for me that would have been the key to human interest - what does the non-transitioner make of the fact that their loved one's body has evidently been taken over by someone from a parallel world?

I can't deny Banks' narrative gifts but Transition has put me off any of his overt sci fi and I shall carefully check the nature of any of his straight novels before taking the plunge again.

Wednesday, 2 December 2015

The Strangler Vine - M J Carter

The Strangler Vine is the first novel by Miranda Carter, biographer of Anthony Blunt and author of The Three Emperors, an account of Queen Victoria's grandsons and how their relationships contributed to World War I.

For a first novel The Strangler Vine is an astonishing achievement. Carter says she knew nothing about India in the 19th Century before starting the project. By the end, clearly, she knew more or less everything. The level of detail is just right. We never get any sense of contrivance, avoidance or - just as fatal in a novel - showing off.

The story inevitably has hints of Kipling and John Buchan. The blurbs cite Sherlock Holmes but it is much better than that (Conan Doyle is a martyr to contrivance and bodge). The year is 1837 and young William Avery, a neophyte and impoverished officer in the private army of the East India Company, is paired up with lapsed agent Jem Blake to go in search of Xavier Mountstuart, the Byrom of India. Avery is a huge fan of Mountstuart, whose work inspired him to seek his fortune in India. Blake was Mountstuart's protege back in the days before he trading spying for literature.

The quest is multi-layered. Nothing is as it first seems as Blake and Avery probe to the black heart of corruption in the Company. The revelations keep on coming, alongside rip-roaring adventure and a sensitive portrait of India clinging to its last vestiges of independence.

I can't wait to lay hands on the second Blake and Avery, The Infidel Strain.

Wednesday, 25 November 2015

Magnus Merriman - Eric Linklater

Magnus Merriman (1934) is Linklater's comic take on early literary fame and Scottish politics. Linklater was familiar with both: his third novel Juan in America, also reviewed on this blog, had been a considerable success and on the back of it (with a nudge from his friend Compton Mackenzie) Linklater stood as the very first Scottish Nationalist candidate in the East Fife parliamentary by-election of 1933 - with a similar catastrophic result to that suffered by his hero here. Linklater lost his deposit with only 3.6% of the vote. Even the candidate for the Agricultural Party got five times more than him.

For me, as a political activist, the first third of the book, with its raucous scenes of Edinburgh nightlife and the local literati, is the most entertaining. The rabid poet Skene is easy to identify in reality but I would love to know who some of the others are, especially Meiklejohn, the journalist who lends his dress trousers.

Merriman's sex life is quite breathtaking for the period and one wonders how much of that is based on the author's experience. It is noteworthy that he married in 1933 and Merriman is probably the first book written after his marriage. His wife Marjorie, to whom the novel is dedicated, is clearly not the model for Rose, the farmer's daughter Magnus marries in Orkney. The Orkney episodes make up and second and much of the third 'acts' of the book. The tone changes, awkwardly but not unpleasantly, as Magnus rediscovers the beauty of his homeland, its simple rustic pleasures and, ultimately, Rose. In between is a brief return to London where Magnus writes journalism for a newpaper owned by Lady Mercy Cotton. Lady Mercy and girl-reporter Nelly Bly both apparently figure in Linklater's earlier novel Poet's Pub, which I haven't yet read. Again I cannot guess who her real-life parallel was.

I continue to enjoy Linklater. His politics are not mine but there is material here which, 80 years on, is just as accurate in its condemnation and outright abuse of the political classes. Linklater is a conservative but his not the Thatcherite free-market, greed-is-good, greed-is-great brand. No, Linklater is an old-school conservative of freedom, honesty and fair play. He is a good sort and good company.

Tuesday, 17 November 2015

King of the Badgers - Philip Hensher

Hensher's defining strength is for building narratives of community, Northern working class in The Northern Clemency and West Country genteel here in King of the Badgers. Clemency also had the advantage of being set against a background of the Thatcher reign of terror, all of which, naturally, could be viewed from hindsight; Badger on the other hand is set and written at the beginning of the Age of Austerity where the outcome can only be guessed at. Thus Clemency is driven by what we know is waiting for our characters, Badger has to have a genre device, a missing child, to propel its narrative.

The setting is the picturesque estuary town of Hanmouth in Devon. In Hanmouth proper the houses are worth £1m apiece, the shops are all craft and there are CCTV cameras everywhere, thanks to Mr Calvin and his influential Neighbourhood Watch. People here who work for a living do so elsewhere - in London or at Barnstaple's third-rate university. The daytime, weekday residents are mostly retired. None of them were born in the houses they now live in.

Out beyond the big roundabout there is another, less fragrant Hanmouth, a massive estate of social housing, which is where single 'mom' Heidi O'Connor lives with her brood. Her second daughter, China, is the one who goes missing. Because Heidi is telegenic, the national Press Pack descends and goes into overdrive. Because the Ruskin estate is anything but telegenic, it is old Hanmouth that is overwhelmed. When direct news dries up the coverage turns speculative. What if Heidi set up the so-called abduction and her skanky ex, Marcus, is hiding China while Heidi cashes in? Before we know it, that is the approved version of events and Heidi is remanded, awaiting trial. Then Marcus is found murdered. And still there is no sign of China.

The thriller narrative effectively ends there, at the end of Act One, though it is resolved three hundred pages or so later. Hensher's second theme is the gay community in Hanmouth, which centres on Sam, the artisan cheesemonger, and his husband Harry, aka Lord What-a-Waste. They belong to a group of bears who meet regularly for food and orgies. We then move to David in St Albans, who writes purposefully unreadable copy for Chine fashionistas who want to be seen with English novels. His parents have moved to a flat in Hanmouth, leaving shy, fat, gay David alone. Then, miraculously, he manages to attract the attention of Mauro, a Soho waiter. David lends Mauro money. Mauro agrees to pose as David's boyfriend during a weekend with his parents in Devon. This happens to be the weekend that Sam and Harry are hosting the bears. Anarchy, sex and profound unhappiness ensue.

The narrative is complex but expertly interwoven. The style is traditional English comic, wherein Hensher excels because he has the rare ability to mock himself without overindulgence. His cast of characters is well-rounded and he holds our attention by gradually peeling off the onion-skin layers of gentle deceit and polite hypocrisy at what always seems like the perfect moment.

Hensher is building a major body of work in which King of the Badgers is a significant milestone.

Monday, 9 November 2015

The Best Short Stories - Rudyard Kipling

Kipling is such a difficult writer to pin down. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature, but wrote only one novel; he celebrated British Imperialism but was in no sense blind to the squalor in which so many of its citizens lived; he often seems misogynistic yet in so many of his stories he celebrates strong, capable women; he is at home in a very personal brand of mysticism yet is utterly fascinated by the latest technology of his day; he is best known for his anthropomorphic tales (Jungle Book etc,) but can also produce a piece as startlingly and subtly original as any post-modernist.

Now, I hated two of the anthropomorphic tales here - "The Ship that Found Herself" and (ugh!) "Below the Mill Dam", which was so cloyingly twee, I couldn't force myself to the end. "The Maltese Cat", on the other hand, I found tolerable in that at least it was about an animal, which we can all accept has a certain level of thought process and, furthermore, it was set in India, which Kipling knew so well. There are naturally several Indian tales here. For me the best was "At the End of the Passage", which is about the downside of working in colonial service.

There are tales of the macabre, notably "Wireless", which exemplifies Kipling's blend of mysticism and modernity, with the titular wireless somehow channeling the spirit of the poet Keats (who was a qualified apothecary) into the soul of an Edwardian pharmacist and fellow consumptive. 'They' was profoundly affecting - a ghost story in which the presence of dead children is a cause for celebration. Again, it is the narrator's up-to-the-minute motor car which attracts the inquisitive spirits. 'They' really is a beautiful piece of work.

The two best stories, though, are "The Finest Story in the World" and "Mrs Bathurst". I think most Kipling readers would agree on the merits of the latter. The former is still very clever and layered - a wannabe writer tells a more experienced hand about his idea for a story. The narrator, recognising the potential of the idea, buys the rights for a pittance. But the youth falls in love with a shop girl and cannot remember how the story ends. The misogyny and the snobbery implicit in the device is, I accept, a major flaw. It's ironic, given that the next story in this collection, "The Record of Badalia Herodsfoot" is a slice of life at its rawest, set in the London slums, in which Badalia is strong, honest and honourable, despite her circumstances.

As for "Mrs Bathurst" - what a marvel it is. Mrs B is a widow based in New Zealand whose fame has spread through the Empire. She is indirectly recalled by an ill-assorted group of men who happen to come together in South Africa. She herself only appears in an early cinema film of people getting off a train in London - a moment of sheer genius on Kipling's part, again showing his fondness for the latest gadgetry. The end is both startling - two unidentifiable human figures reduced to charcoal by lightning - and inconclusive. There is nothing to say if either victim is the lady in question or her apparently final lover. The story's power lies in its elusiveness. And its power is extraordinary. I cannot stop thinking about it, three days after reading it.

Regular readers of this blog will know that I am not a fan of introductions to books. I make an exception for that of Cedric Watts in this instance. He is especially useful on "Mrs Bathurst". I read his comments both before and after reading the story itself.

Thursday, 5 November 2015

Jeremy Hutchinson's Case Histories - Thomas Grant

Jeremy Hutchinson is 100 years old. He has been a barrister since 1945, a Queen's Counsel since the early sixties and a life peer since 1978. He is a scion of the Bloomsbury set and a lifelong patron (and defender) of the arts. He stood as the Labour candidate for the hopeless Westminster Abbey seat in the 1945 General Election.

Thomas Grant is also a QC and what they have come up with in this book is a social history of postwar Britain seen through the lens of celebrated court cases in which Hutchinson led the defence. These include the spy trials of George Blake and John Vassall, the Profumo Affair in which he represented Christine Keeler, various obscenity cases including Lady Chatterley's Lover and The Romans in Britain, the art fraudster Tom Keating and the drugs smuggler Howard Marks. Grant has cleverly grouped these by subject because his aim is not a comprehensive or chronological life of his subject. That said, he does begin with an excellent short biography, which I thought was nigh on perfect.

The highlight, though, is the postscript by the great man himself, whom great age has in no sense withered. Indeed, he seems to have written it in his centenary month (March 2015). Here he takes a swipe at the consequences of Legal Aid cuts and the attempts of the then Lord Chancellor, Chris Grayling, to undermine the fundamentals of British justice. Hutchinson, the great libertarian, takes the 'savings' apart with consummate, even deadly, skill. He ends with the obvious and proper solution to ballooning budgets at the Ministry of Justice:

[The MoJ] has only to attend to another area of its responsibility: the crisis in our intolerably overcrowded prisons. The prison population has now grown to over 85,000 (it was 46,000 when I retired). Each of these prisoners costs the taxpayer around £40,000 a year to keep. The 'warehousing' and humiliation of offenders in grossly full and inhuman conditions make meaningful education, constructive work, rehabilitation and self-respect impossible. It produces inevitable recidivism and lowers the morale of the overworked and dedicated staff. Governors repeatedly point out that they have to cope with thousands of inmates who should not be there at all: the mentally ill, the drug takers, those serving indeterminate sentences under a law now long repealed, unconvicted defendants in custody awaiting trial for minor offences for which they clearly will not receive a custodial sentence. ,,, Real prison reform calls for imagination, courage and determination; the dismantling of legal aid a mere stroke of the pen.In case you think this is Hutchinson's Labour bias (or mine, for that matter), let me also quote his onslaught on New Labour's so-called 'reforms':

In 2003 Tony Blair, supporting his autocratic and oppressive Home Secretary David Blunkett, without consultation or advice, sacked his protesting Lord Chancellor, Lord Irvine, and abolished the office itself. Thus, on the whim of an arrogant and power-hungry politician the second greatest office of state was destroyed, after 800 years.This is how great lives should be lived and recorded. My book of the year thus far. Essential reading.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)