Total Pageviews

Monday, 30 December 2019

Killing Eve - Codename Villanelle - Luke Jennings

Everyone knows Killing Eve. Everyone watched the first series, considerably fewer went the distance with the second. Luke Jennings is the creator and wrote the original ebooks. Codename Villanelle is the collection of the first four (the titular first, 'Hollowpoint,' 'Shanghai,' and 'Odessa'. The good news is there are two more collections to get my greedy mitts on. The even better news is that the originals are just as good as the first TV series. Phoebe Waller-Bridge dispensed with some of the story and added other elements, but overall the punchy structure, the offbeat dark humour, the wit and the downright beauty were all kept. The lack of wit is where the second series probably went wrong.

The problem Waller-Bridge had was that Sandra Oh cost big money but she doesn't feature in the first installment, 'Codename Villanelle.' So she had to be inserted from the start. 'Killing Eve' may well become Villanelle's obsession in the successor volumes, but it isn't the plot driver here, which makes the title slightly odd. These are minor quibbles, though. I loved every minute of reading this. Luke Jennings is a master of the shorter form. Every word counts. He lingers on evocative detail, like the shoes Villanelle is wearing when she kills. He also creates wonderful images - there is a magnificent phrase about a snow-filled umber sky over grey trees - but he knows his main job is to get on with the action.

This is where comments about Villanelle being a 'female James Bond' suddenly become apposite. Fleming was a rotten writer who made up for his lack of talent with knowledge of cars and guns and exotic locations. Jennings, who I stress again is a brilliant writer, does cars and guns and exotic - but he also adds opera and Paris fashion shows and perfumes. To put it bluntly, the man's a genius. For me, 'Shanghai' is a mini masterpiece.

Friday, 27 December 2019

To the Top of the Mountain - Arne Dahl

Arne Dahl is the pen-name of Jan Arnald. To the Top of the Mountain (2000) is the third of his ten-novel A-Unit series, featuring a select team of special investigators working out of Stockholm. The A-Unit has been disbanded as we start this novel. Paul Hjelm and Kerstin Holm are still in Stockholm but now reduced to handling routine inquiries - like the young football fan who has a glass smashed on his skull in a dingy bar. This is the crime that starts everything rolling, but it has nothing to do with the main narrative. It turns out that everyone else in the bar - everyone who is not a football fan, attending a hen party, scoping out the hens or other chickens in the case of the famous Hard Homo - is part of complex overlapping conspiracies. The next thing we know a second rate gangster is blown up in his prison cell and emissaries of the principal gangster are gunned down by fascists. The main story is under way and the A-Unit is re-established to sort it all out.

This is one of the traits I like most in Arne Dahl - the way the story rolls out in all directions, to be gathered neatly together in the end. His characters are also compelling. We have the characters we already know (either on TV or in Europa Blues, the other Arne Dahl I have read and reviewed here): Hjelm and Holm, the star-crossed lovers; the Finnish thinker Arto Soderstedt; the new and unexpected midlife father Viggo Norlander; ambitious immigrant Jorge Chavez; and Sweden's biggest policeman Gunnar Nyberg, played on TV by the World's Strongest Man (1998), Magnus Samuelsson. At the start of this novel Gunnar is working for the paedophile police. He doesn't like the work but he is committed to rounding up the perpetrators. Initially he is only prepared to return part-time to the A-Unit. This introduces new characters, notably Sarah Svenhagen, daughter of Chief Forensic Technician Brynholf. Sara is investigating a highly secretive lead which ultimately leads to the unravelling of the over-arching case. Sara is a magnificent character. By the quarter-point I was captivated by her.

I liked Europa Blues. I watched and enjoyed both series of Arne Dahl on BBC4. But To the Top of the Mountain is better than Europa Blues, partly because it explores the psychology of its characters to an extent that's just not possible in TV adaptations. Arne Dahl is a major player in contemporary crime fiction.

Thursday, 19 December 2019

Trinity Six - Charles Cumming

I don't understand why Charles Cumming isn't promoted on the same scale as John le Carre, because he certainly is the frontrunner to inherit the great man's position as number one scribe of British spycraft.

Trinity Six is closer to home than most of Cumming's work, Britain-based, albeit his protagonist, UCL lecturer Sam Gaddis, gets about during the course of his fictional journey. He kind of inherits a project about the much-mooted sixth man of the Thirties communist cell at Trinity College Cambridge. He meets the man in the know (or is he?) and begins his research - only to see a key witness gunned down in front of him, only for Gaddis himself to gun down the assailant.

It seems the British SIS is not the only organisation of its ilk with an interest in suppressing the Sixth Man story. The revelation of why is splendid when it comes. The working out of the plot - a fine example of the biter bitten - is masterly. What is wrong with British TV? Why is nobody snapping up Cumming's work for must-see broadcasting?

Wednesday, 18 December 2019

The Reflection - Hugo Wilcken

A cracking little twist on a noir meme, this. Taking his cue from John Franklin Bardin's The Deadly Percheron, which I must re-read, Wilcken conjures up a Kafka-esque nightmare in which Manhattan psychiatrist David Manne finds himself with the identity of a man he himself has committed to the mental hospital. Is he the victim of a conspiracy or is one - or both - identity a delusion? Wilcken tangles his web brilliantly, leaving us with no real answers, only questions. I loved it.

Friday, 13 December 2019

Broken Ground - Val McDermid

It was my intention to read the Karen Pirie novels in order but Broken Ground is the fifth, published in 2018. Fortunately McDermid is so skilled that it makes no real difference - she updates the reader on what they need to know, which is that Pirie's partner has been killed and she is in a period of bereavement.

The business of the Historic Cases Unit goes on however. At first it seems the body found alongside two wartime Harley Davidson motorbikes is outside the unit's remit. They only deal with deaths less than seventy years old in which there is a realistic chance of relatives and witnesses who are still living. Closer examination reveals the dead man is wearing trainers from 1995. Pirie and her gormless assistant Jason 'The Mint' Murray enter the world of wartime double agents, contemporary professional strongmen and motorhome etiquette of the mid-nineties.

The plot rolls out over 500 pages which unfold like a dream. I didn't much like the flashbacks but they were effective enough as a device for delivering the back story. I thoroughly enjoyed the development of the main characters and I especially enjoyed McDermid's daring finale in which Karen arrests her suspect but all her problems are left hanging for the next installment. So what am I supposed to do now, Val, if I find myself looking at Volume 2 and Volume 6? I know, the answer is obvious (get both), but which do I read first?

Saturday, 7 December 2019

Strangers on a Train - Patricia Highsmith

Strangers on a Train was Highsmith's debut in 1950 and, filmed by Hitchcock a year later, made her name and her fortune. I was therefore excited to come across this nicely put-together Vintage edition. I had never read any Highsmith, but surely I should, given my abiding interest in American noir. Well, now I have and I have to say I am very disappointed.

The premise is, of course, brilliant. Complete strangers meet on the titular train and agree to murder one another's victim. What can possibly go wrong? What's not to keep us turning those pages all the way to denouement?

Well, the sheer number of pages, for a start. The novel is at least 30% too long. There isn't enough story to keep us interested, the characters are too simplistic (hard-working genius and hard-shirking rich wastrel), and the writing is too overwrought. Frankly I didn't care how they got their come-uppance, I just wanted it to end.

Surely the beauty of classic noir is brevity, whereas Highsmith gives us page after page of obvious filler, almost as if she is getting paid by the word. There is, to be fair, a stab at psychological insight, however I was not convinced. The women characters, in a novel by a woman, are so poor as to border on misogyny (tart, tart and doormat). There is literary style but it is stilted and occasionally perversely anachronistic. What I suppose is meant to be the final twist - how the detective gets Haines' confession, is too hackneyed even for an old-fashioned stage thriller and wouldn't have stood up as evidence in any court even in 1950. Had I not been bored stiff by that point, I would have laughed.

Thursday, 5 December 2019

James Whale - Mark Gatiss

This biography of the Hollywood director behind Show Boat and Frankenstein was written in 1995, about the time Gatiss started with The League of Gentlemen. Whale is fascinating. He seemed to be the archetypal English gent but in fact he rose from considerable poverty in the industrial West Midlands. He was almost 40 when he took to directing at all, and hit the jackpot first time when his production of R C Sheriff's Journey's End went from pro-am to the West End, then Broadway, then for most of those involved, Hollywood.

Whale enjoyed a decade of spectacular screen successes before abruptly falling from sight. By the time America entered World War II he was more or less unwillingly retired. He took to painting and then drowned himself in his pool aged 68.

Whale's problem, of course, was that he was homosexual, not overtly but certainly not covertly. Everyone knew but not everybody had a problem. But when Whale became a problem in other areas of activity, too demanding on set, not sufficiently deferential to the new studio owners, his homosexuality was used as an excuse to get rid of him. They stopped him working but in many ways Whale had the last laugh. He always seemed to know his time in the spotlight was limited. He looked after his money when he was as highly paid as any director in town. After almost twenty years living off his savings in considerable style, he still managed to leave an estate worth over half a million dollars.

Gatiss, we all know, is a gifted writer who does his research, The book is sheer joy to read, from start to finish.

Tuesday, 3 December 2019

The Temple of Dawn - Yukio Mishima

The Temple of Dawn is the third part of The Sea of Fertility tetralogy. I would clearly of benefited from reading the preceding two first. All the same, I found The Temple of Dawn fascinating in itself as a chronicle of man in later middle age coming to terms with mortality by means of an extraordinary exploration of reincarnation as envisaged in various forms of Buddhism.

Honda is a distinguished lawyer and former judge. In 1939 he is sent to Bangkok to resolve a commercial dispute. Whilst there he is introduced to Princess Moonshine, a peripheral member of the royal family and a greatly cosseted infant. The strange thing is that she seems to understand Honda, who speaks only Japanese, and seems to suggest that she is a reincarnation of Matsugae, Honda's schoolfriend (this is essentially the plot of the novel sequence - Honda trying to save successive reincarnations of his friend).

Having won the lawsuit, Honda is rewarded with an expenses-paid tour of India, where he investigates the reincarnation belief. This is done in extraordinary detail and again, I suspect that this is the culmination of previous theorising in earlier books; in this book, considered alone, it goes on too long. Certainly a disproportionately tiny amount of space is given here to World War 2, which can't be right.

After the war, fifteen years after their first meeting, Honda meets the princess again. Now known as Ying Chan, she is studying in Japan. Honda's mission now is to find out if she has Matsugae's telltale triangle of moles on her side, beneath her arm. He goes to ludicrous, even perverse lengths - a man pursuing his obsession.

There is masterly writing here. We encounter Mishima at the height of his powers - and he was a great writer to begin with. I shall certainly track down the other three volumes of The Sea of Fertility, but perhaps something a little less demanding first.

Honda is a distinguished lawyer and former judge. In 1939 he is sent to Bangkok to resolve a commercial dispute. Whilst there he is introduced to Princess Moonshine, a peripheral member of the royal family and a greatly cosseted infant. The strange thing is that she seems to understand Honda, who speaks only Japanese, and seems to suggest that she is a reincarnation of Matsugae, Honda's schoolfriend (this is essentially the plot of the novel sequence - Honda trying to save successive reincarnations of his friend).

Having won the lawsuit, Honda is rewarded with an expenses-paid tour of India, where he investigates the reincarnation belief. This is done in extraordinary detail and again, I suspect that this is the culmination of previous theorising in earlier books; in this book, considered alone, it goes on too long. Certainly a disproportionately tiny amount of space is given here to World War 2, which can't be right.

After the war, fifteen years after their first meeting, Honda meets the princess again. Now known as Ying Chan, she is studying in Japan. Honda's mission now is to find out if she has Matsugae's telltale triangle of moles on her side, beneath her arm. He goes to ludicrous, even perverse lengths - a man pursuing his obsession.

There is masterly writing here. We encounter Mishima at the height of his powers - and he was a great writer to begin with. I shall certainly track down the other three volumes of The Sea of Fertility, but perhaps something a little less demanding first.

Wednesday, 27 November 2019

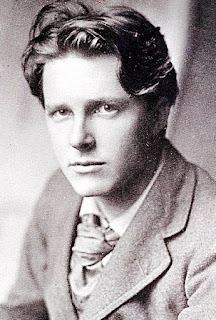

Rupert Brooke, Life, Death and Myth - Nigel Jones

Jones's book, first published in 1999 and revised for this Head of Zeus edition in 1915, is the most up-to-date study of the poet. Like Lehmann (reviewed below) it has the advantage of being written after all the guardians of the flame (the Brooke Trustees) had died and relinquished their stranglehold, but Jones rather tarnishes the freedom by making Brooke as unpleasant as possible. Some of Brooke's behaviour, particularly to women, is shameful - but I wonder, weren't we all like that when we were young and naive? Brooke was only 27 when he died, which admittedly is not all that young, but he was still financially reliant on his mother and surrounded by friends, would-be lovers and general sycophants who surely retarded the development of his character. Having now studied dozens of books on him in the last three months, I am of the opinion that Brooke only approached man's estate after his last tour to America and Canada and the South Seas in 1913-14. His behaviour seemed to moderate (Maurice Browne's 1927 Recollections are helpful in this, as he only met Brooke in 1914) and people started to see him as a man rather than a gilded youth. Certainly his poems mature considerably between Georgian Poetry (1911) and the war Sonnets (1914).

Jones's book is also absurdly long at 564 pages. You simply cannot justify that level of wordage for a man who died at 27. Equally, there are only so many times you can criticise the stifling hand of his patron Eddie Marsh and the Trustees under his lifelong friend Geoffrey Keynes. Both these men were successful and important in their own right. They believed - genuinely - they were acting in Brooke's best interests at the time and, given that neither disposed of the less flattering material, I believe it is reasonable to suppose that they realised attitudes would change in later years. Keynes was still alive when Michael Hastings produced his iconoclastic work, The Handsomest Young Man in England in 1967, and nobody tells Hastings what to write.

In summary, everything you could possibly want to know about Rupert Brooke is here in Jones. You might want to moderate Jones's rather black and white judgments a little with Lehmann and a look at Hastings (essentially a picture-book interspersed with very interesting commentary). If you can find a copy (it was privately printed) Browne is a startling insight into the modernist world that Brooke also enjoyed. Chicago is, after all, a long way from Grandchester.

Tuesday, 26 November 2019

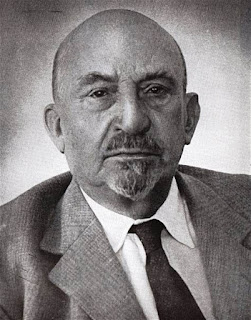

The Sun Chemist - Lionel Davidson

How on earth do you make a thriller out of writing footnotes for the letters of Israel's first president? Lionel Davidson shows how. Igor Druyanov, a historian of Russian descent, is commissioned to prepare a couple of installments of the massive multi-volume Letters of Chaim Weizmann (1874-1952). The years in question were Weizmann's wilderness years - like Churchill, these were the Twenties and Thirties - when he was ousted from the Zionist movement and had to revert to his original profession as a research chemist.

The key to the tension here is that the book dates from 1976 and begins a couple of years earlier, in 1974. This is when OPEC jacked up oil prices, creating a crisis in the West and making the polite, ever-smiling Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani a hate figure. At rhe time it seemed as if the greedy, ungrateful Arabs were threatening the developed world with a new stone age. Indeed, the West has spent the last fifty years developing alternative power sources to avoid a repeat, whilst the Arab world has taken a more moderate line in exploiting what is, after all, their only real resource, and a finite one at that.

But Davidson's book is firmly anchored in 1974-6 and the Israel of that time, a year or so after the first Arab-Israeli war. Davidson might have been born in Hull but at this time he was living in Israel. In the story, it emerges from Igor's research that Weizmann and his research associates might have hit upon a way of synthesizing combustible fuel from root vegetables. It isn't quite so simple, and Davidson spares us none of the science, but that is essentially it: an infinite supply of fuel to a power-hungry world; a windfall beyond price to a state just establishing itself in the deserts of Palestine and the end of time to their near neighbours in the Gulf.

It's a great book and an astonishing feat of writing from Davidson. He was never a scientist, always a journalist but, by God, he does his research. Every part of the book, from the history that drives Druyanov, to the world of international science and petrochemicals, is utterly convincing. Davidson, to be fair, was a peripatetic journalist and, as I say above, lived in Israel - but I've never read anything, fact or fiction, that brings that raw state so alive. Davidson, in my view, is even better than Ambler, better than Greene, and so unusual in his choice of subjects. He deserves to be better remembered than he is. As for this book, is there a thriller in print today that is more topical?

Sunday, 17 November 2019

The Silence of the Girls - Pat Barker

I was a big fan of the Regeneration Trilogy, not quite so keen on the Life Class Trilogy, although I still enjoyed it. Neither prepared me for this. The Silence of the Girls is a masterpiece - it's as simple as that. Barker takes the exact same episode of the Trojan War that Homer does, the 'wrath of Achilles', and does it from the woman's point of view. Given that Agamemnon's depriving Achilles of his prize slave Briseis, the captured queen of Trojan Lyrnessus, prompted the long sulk, this is an even better concept than Homer's. We see everything from all sides, Greek, Trojan, man, woman. And the change that Briseis brings about in Achilles, after the death of Patrocolus, is beautifully done by Barker and utterly convincing. I also loved the way she depicted the hero's eerie mother, the sea-nymph Thetis. That said, all her characterisations worked for me: the aged Priam, the simple Ajax, the individual enslaved women, and best of all, ever-patient Patrocolus. There is nothing more I can say. The best book I have read this year. A true work of art. I relished every single word.

Thursday, 14 November 2019

A Wrinkle in the Skin - John Christopher

A Wrinkle in the Skin, A Terrible Title, is a 1965 disaster novel by John Christopher (Sam Youd), creator of the Tripods and author of the classic The Death of Grass.

Christopher has enjoyed something of a revival since his death in 2012. He is regarded as a prophet of ecological disasrer, which is certainly the case with The Death of Grass and The World in Winter. A Wrinkle in the Skin is certainly global but the disaster is not man-made. Vast earthquakes have reshaped the Earth, to the extent that the English Channel has dried up. The tidal wave that accompanied the quakes has wiped away coastal cities like Southampton and Bournemouth.

Our hero, Matthew Cotter, grows tomatoes on Guernsey. The quake makes a mess of his glasshouses but he is unscathed. He wanders about the island and finds others who have survived. They are very few, but they group together, find food and start to make a sort of life. Matthew, however, is determined to find his daughter Jane who he knows spent the night of the apocalypse in East Sussex. So he sets out to walk there, there being no deep water to stop him., accompanied by the orphaned boy Billy.

This is unfortunate - mature man and immature child on a mission of discovery has become a cliche of post-apocalyptic fiction (The Road, for example). To be fair, Christopher wrote in 1965 and I'm pretty sure it wasn't a cliche back then. So they meet a mad king (actually a sailor, the solitary survivor on an oil tanker stranded on the dry bottom of the Channel, desperately trying to keep everything literally shipshape. They meet a Preacher, a visionary of the apocalypse who foresees the Risen Christ approaching from the East. And they meet other groups, good and bad and extremely bad. It's all a bit predictable - except that I liked the ambition of making the ship a supertanker, I liked that the religious crazy was a hospitable host, and I really liked April, the sole female character who is fully characterised. There is a conversation between April and Cotter which is both shocking and moving - which inspires Matthew to pursue his quest to the bitter end (another excellent twist) and the scales to finally fall from his eyes.

A good book, then, not as significant as some of Christopher's others but effective and skillfully done.

Christopher has enjoyed something of a revival since his death in 2012. He is regarded as a prophet of ecological disasrer, which is certainly the case with The Death of Grass and The World in Winter. A Wrinkle in the Skin is certainly global but the disaster is not man-made. Vast earthquakes have reshaped the Earth, to the extent that the English Channel has dried up. The tidal wave that accompanied the quakes has wiped away coastal cities like Southampton and Bournemouth.

Our hero, Matthew Cotter, grows tomatoes on Guernsey. The quake makes a mess of his glasshouses but he is unscathed. He wanders about the island and finds others who have survived. They are very few, but they group together, find food and start to make a sort of life. Matthew, however, is determined to find his daughter Jane who he knows spent the night of the apocalypse in East Sussex. So he sets out to walk there, there being no deep water to stop him., accompanied by the orphaned boy Billy.

This is unfortunate - mature man and immature child on a mission of discovery has become a cliche of post-apocalyptic fiction (The Road, for example). To be fair, Christopher wrote in 1965 and I'm pretty sure it wasn't a cliche back then. So they meet a mad king (actually a sailor, the solitary survivor on an oil tanker stranded on the dry bottom of the Channel, desperately trying to keep everything literally shipshape. They meet a Preacher, a visionary of the apocalypse who foresees the Risen Christ approaching from the East. And they meet other groups, good and bad and extremely bad. It's all a bit predictable - except that I liked the ambition of making the ship a supertanker, I liked that the religious crazy was a hospitable host, and I really liked April, the sole female character who is fully characterised. There is a conversation between April and Cotter which is both shocking and moving - which inspires Matthew to pursue his quest to the bitter end (another excellent twist) and the scales to finally fall from his eyes.

A good book, then, not as significant as some of Christopher's others but effective and skillfully done.

Monday, 11 November 2019

Rupert Brooke, His Life and Legend - John Lehmann

I have been reading a lot about Rupert Brooke lately, in connection with a couple of personal projects of which, hopefully, more later. There are a fair few works on Brooke but the vast majority suffer from an obvious problem - length. Brooke was astonishingly busy, he wrote a lot from an early age, he had an enormous social circle and he travelled the world. But even so, he was only 27 when he died, and you simply can't justify 500+ pages for a life that short.

John Lehmann (1907-87) came of an astonishingly intellectual and creative family. His sister Rosamund was a novelist, his sister Beatrix a highly-celebrated actress. John was a poet and publisher. He founded New Writing in 1936, became a managing director of the Hogarth Press in 1938 and founded his own firm, John Lehmann Limited, in 1946. Finally, in 1954, he started The London Magazine. It's all very close-knit, a bit incestuous, and a bit artsy-craftsy. Which made him the perfect author for a critical biography of Rupert Brooke, who was a beneficiary and part-creator of similar arrangements before his ludicrous death in 1915. Best of all, Lehmann can do in 170 pages what Brooke's other biographers can't manage in several hundred pages. He brings Brooke alive in all his contradictory aspects - obsessed with women but offensively dismissive when the mood takes him; flirting with homosexuality but keeping his patron Eddie Marsh, who worshiped him, at a very resolute arm's length; globetrotting but always trying to micromanage his English friends. He was not a nice man but he was extraordinarily beautiful. He was a talented poet, more gifted than most in his day but did not live long enough to become truly great. And, as Lehmann says, he has been abandoned by the lirerary world which prostrated itself before his metaphorical shrine in 1915, in favour of those who came shortly after him and who lived long enough to experience the true horror of mechanized war: Sassoon, Owen and Graves.

Lehmann treats Brooke's service in a respectful and fair manner. Brooke was a volunteer, as everyone was in 1914. He did not ask Marsh, who was Churchill's secretary, to get him a safe billet in the Royal Navy Voluntary Reserve and it soon proved not to be particularly safe. Lehmann is better than most is describing Brooke's single experience of being under fire, in the long-forgotten farce of the British attempt to relieve the German siege of Antwerp. And let us not forget that Brooke was en route for the Dardanelles and the mass slaughter of Gallipoli when sunstroke did for him.

For anyone wanting to dip their toe into Brooke studies and come away with solid facts and a sound appraisal of his achievements, I cannot recommend Lehmann too highly.

John Lehmann (1907-87) came of an astonishingly intellectual and creative family. His sister Rosamund was a novelist, his sister Beatrix a highly-celebrated actress. John was a poet and publisher. He founded New Writing in 1936, became a managing director of the Hogarth Press in 1938 and founded his own firm, John Lehmann Limited, in 1946. Finally, in 1954, he started The London Magazine. It's all very close-knit, a bit incestuous, and a bit artsy-craftsy. Which made him the perfect author for a critical biography of Rupert Brooke, who was a beneficiary and part-creator of similar arrangements before his ludicrous death in 1915. Best of all, Lehmann can do in 170 pages what Brooke's other biographers can't manage in several hundred pages. He brings Brooke alive in all his contradictory aspects - obsessed with women but offensively dismissive when the mood takes him; flirting with homosexuality but keeping his patron Eddie Marsh, who worshiped him, at a very resolute arm's length; globetrotting but always trying to micromanage his English friends. He was not a nice man but he was extraordinarily beautiful. He was a talented poet, more gifted than most in his day but did not live long enough to become truly great. And, as Lehmann says, he has been abandoned by the lirerary world which prostrated itself before his metaphorical shrine in 1915, in favour of those who came shortly after him and who lived long enough to experience the true horror of mechanized war: Sassoon, Owen and Graves.

Lehmann treats Brooke's service in a respectful and fair manner. Brooke was a volunteer, as everyone was in 1914. He did not ask Marsh, who was Churchill's secretary, to get him a safe billet in the Royal Navy Voluntary Reserve and it soon proved not to be particularly safe. Lehmann is better than most is describing Brooke's single experience of being under fire, in the long-forgotten farce of the British attempt to relieve the German siege of Antwerp. And let us not forget that Brooke was en route for the Dardanelles and the mass slaughter of Gallipoli when sunstroke did for him.

For anyone wanting to dip their toe into Brooke studies and come away with solid facts and a sound appraisal of his achievements, I cannot recommend Lehmann too highly.

Monday, 4 November 2019

Acts of Allegiance - Peter Cunningham

I find myself conflicted over the modern Irish novel, of which this is certainly one. I hate the formulaic family-in-a-misty-soggy-paradise novel which has dominated the Booker for so long. On the other hand there are standout marvels like Roddy Doyle. Peter Cunningham, on the evidence of this novel, falls somewhere between the two.

There are heinous echoes of the formula - the roguish Pa who puts on a front, the matriarch's house which includes people who may or may not be family members. But against that we have the personal story of Marty Ransom who has bridged the border by collaborating with the Brits whilst building a career in the Irish diplomatic corps. And the compelling antagonist of Iggy Kane, Marty's cousin and childhood boon companion.

The balance between the two is not quite right. Cunningham essentially has three storylines going - childhood, young adulthood, and subsequent, ultimate betrayal. The one that doesn't get quite enough play, for me, is the betrayal. We perhaps need just one more example of Iggy's activities in the North before he blasts his way back into Marty's life. That said, the betrayal itself is beautifully done.

Thursday, 31 October 2019

The Streets - Anthony Quinn

London, 1882. David Wildeblood is the new Somers Town correspondent of Henry Marchmont's campaigning newspaper The Labouring Classes of London, a post secured for him (after some personal difficulties) by the godfather he has never met, Sir Martin Elder. Somers Town, for those who do not know, is the site of the future Euston Station. In 1882 it was a warren of decaying housing, a slum but not quite a Dickensian rookery. It is an alien world to the naive young David but he finds a guide, the market trader Jo. He also finds that the local vestry - equivalent, more or less, of a parish council - is comprised of dodgy landlords who actually own the slums, for which they charge extortionate rents. This leads the bold investigator to a larger, more sinister conspiracy, involving forced evacuation of the poor and even eugenics.

The initial premise, the corrupt vestry, was familiar to me, probably from the real-life work of Mayhew and Booth, both of whom Quinn acknowledges as sources,* but where the author then went with it was fresh and startling. Quinn makes his point, which is not a million miles away from the subtext of the Cameron-Clegg coalition in 2012, when he wrote it, without ever cutting back on the literary quality. Quinn is a very fine novelist indeed. Not many contemporary novelists could get away with 'refulgent' but Quinn does, twice.

More important, of course, are his characters, all beautifully brought to life in three dimensions. I was extremely impressed.

* Since writing the above I have remembered where I saw it - Sarah Wise's The Blackest Streets, which is also credited by Quinn and reviewed on this blog.

Sunday, 27 October 2019

The Border - Don Winslow

Winslow - back on top form. Brilliant.

The Border concludes the Cartel trilogy and brings it bang up to date. Art Keller emerges from the Guatemalan jungle to take over as head of the DEA, having realised that the only way to tackle America's drug problem is to take out the big money men. That doesn't just mean the Cartel bosses, because Keller now knows there are people above them on the US end of the chain. For the Cartels drugs mean money and power. For the financiers power can be bought by money. And now they plan to buy the ultimate power.

Meanwhile, the fact that Keller has finally taken out Adan Barrera, head of the Sinaloan Cartel and effective boss of bosses, means that the second tier go to war to determine a successor. The lack of order means there are vacuums for figures from the past to return to: men like Rafael Caro, who tortured and murdered Keller's partner thirty years ago, and Eddie Ruiz who was there when Keller took out Adan.

It is a big, BIG story, and rightly so. In so many ways it is the story of our time, the fifty year war on drugs which America has not and will never win. How close Winslow's fiction comes to reality will be open to debate. What is inarguable, a stone fact, is that nobody does this story better than Don Winslow. Does anybody else even dare to try? Each of the three novels - The Power of the Dog, The Cartel, and now The Border - is a major achievement. The three together are a landmark.

Monday, 21 October 2019

Laura - Vera Caspary

Laura was Caspary's break into the big time. It came out in 1943, having previously been serialised in a magazine, became a Otto Preminger movie in 1944 and a stage play the year after. It is a hard-boiled crime of passion novel with all the qualities of the best literary fiction.

Waldo Lydecker is a New York writer of literary fiction. He is fat, snobbish and affected, with a silly beard and an ebony cane. He is our first story-teller, for Caspary has emulated the Moonstone device of multiple first-person narration. Lydecker is besotted with Laura, as is every man she ever met. Lydecker was seeking to introduce her to art and society, so when she is found dead in her apartment, shot in the bewitching face, Lydecker is the second person Detective Mark McPherson calls on, after Laura's fiance, Shelby Carpenter. Laura and Shelby were due to be married the next week. She had planned a final solo holiday but before she left was due to dine with Lydecker.

The plot is astonishing. My jaw genuinely dropped at the big twist. Caspary drip-feeds the clues like a research scientist breeding bacteria. Everything you need to know is there, none of it apparent without hindsight. The novel is short, exquisitely so, but every word is loaded with meaning. And the style, like the cover art on this Vintage edition, is superb. The following is from Detective McPherson, the fish out of water in the refined circle inhabited by Lydecker, Laura and Carpenter:

Even professionally I've never been inside a night club with leopard-skin covers on the chairs. When these people want to insult one another, they say darling, and when they get affectionate they throw around words that a Jefferson Market bailiff wouldn't use to a pimp. [...] It takes a college education to teach a man that he can put on paper what he used to write on a fence.

Thursday, 17 October 2019

In a House of Lies - Ian Rankin

The odd dud is inevitable when you are as prolific as Ian Rankin, and this is undoubtedly one of his. It seems to be based on two celebrated podcasts about murder, the Adnan Syed case which made Serial a worldwide hit and the murder of Daniel Morgan in London in 1987. Basically we have the murder of a private detective and the key clue about how long a car was parked where it was found which hinges on the analysis of soil and grass. Note to Rankin: You're a crime writer; never assume your crime readers are less informed than you are.

The second problem is that Rankin continues to employ the detective triad which, for me at least, is no longer interesting or indeed credible: Rebus, Malcolm Fox and Siobhan Clarke. It is essentially a good idea. Now he is retired Rebus can be even more of a wild card; Clarke has to obey the rules or her long association with Rebus will hold her back; and Fox polices the police. The problem is, they all come with baggage from up to 21 previous outings, or, in Fox's case, from two novels in which he was the replacement for Rebus. This means a certain number of secondary characters have to revisited, even if there is no plotting need. If Rankin isn't at the very top of his game, this can lead to an imbalance between investigation and back story. Needless to say, in Rebus #22, Rankin isn't at the apex of his ability.

It's readable - Rankin is always readable - but the problems are overwhelming. Both the A plot and the B subplot are fundamentally unbelievable; no one kills or accepts the blame for killing for such trivial reasons. And the novel itself is about 25% too long. I hope Rankin recovers form for the next Rebus. I for one could not take another misfire, especially as recent instalments have been so good.

Monday, 14 October 2019

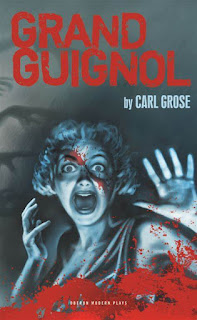

Grand Guignol - Carl Grose

Grand Guignol is a play. Not a Grand Guignol play but a play about Grand Guignol, specifically the creation of the form in the Parisian theatre of that name around 1900. It starts with a performance of such a play which causes the celebrated physiologist Alfred Binet, the inventor of intelligence testing, to intervene. He simply cannot contain himself and leaps up onstage, breaking the illusion. He gets introduced to the Prince of Terror, Andre de Lorde, otherwise a shy, unassuming librarian and they start to collaborate. Ultimately they conceive the most outrageous of classic Grand Guignol (certainly in England), Crime in a Madhouse.

The performance switches between actual performance and the actors who are doing the performance. Everything we need to know about Grand Guignol in order to follow the action is provided. It is more or less accurate - Grose in his acknowledgements cites the best known authorities on the form, Mel Gordon, Richard Hand and Michael Wilson. There is what I felt was an unnecessary subplot and one rather clumsy in-joke. Other than that, the play is great fun and I would love to see it live.

Grand Guignol was first performed in The Drum at the Theatre Royal Plymouth on October 29 2009.

Tuesday, 8 October 2019

Goldstein - Volker Kutscher

Goldstein is the third of the Gereon Rath novels, not to be confused with the forthcoming third series of the Babylon Berlin TV series, to which the only resemblance is the appearance of Gereon Rath and the Weimar Republic.

The titular Goldstein is an American mob assassin of German Jewish heritage, who pitches up in Berlin in 1931. Rath, having blotted his copybook once more, is given the job of tailing him. Meanwhile someone is killing proto-Nazis, including cops, and Rath is specifically excluded from the investigation - which, of course, means he solves it.

Kutscher's series has been an international hit, in print and more so on TV, the latter because it contains a great deal of sexual material which is absent from the books. The fact remains, though, that Kutscher is not making the techical development he should be. Goldstein is by far the most interesting character here, but disappears for most of it. Rath's sideline working for the gangster Johann Marlow is this time little more than perfunctory.

The book starts off great, with two teenage burglars robbing a major store, but rapidly goes flabby. I enjoyed The Silent Death more than Babylon Berlin but I enjoyed both of them more than I enjoyed Goldstein. Not a good sign for the future.

Tuesday, 1 October 2019

The Wolf and the Watchman - Niklas Natt och Dag

An extraordinary achievement, fully deserving all the hype it has received, The Wolf and the Watchman is certainly the historical novel of the year, possibly the best since The Name of the Rose, back in the Eighties.

The story itself is startlingly original. In Stockholm, in 1793, the one-armed watchman Mickel Cardell pulls a dead man from the water. I was originally going to say body but that is somewhat of an overstatement in the case of this man. His arms, legs, eyes, tongue and teeth have all been removed, in stages, before death. The under-pressure police chief summons his friend and sometime investigator Cecil Winge. Winge has solved potentially unsolvable cases before, and if he doesn't succeed this time, he has nothing to lose, given that he has already outlived expert estimates of death from consumption.

Cardell and Winge join forces, the former providing the physicality to the latter's brains. Of course they eventually find out the dead man's identity and who killed him, but not before the author has opened up the story in an amazingly bold way.

The story starts in Autumn 1793 but then goes backwards in time, first to the summer. This is the story of the teenaged surgeon's assistant Johan Kristofer Blix, who we are meant to assume is the mutilated victim. Blix falls foul of the wastrel elite and builds a substantial debt which is then sold on to a nobleman who carries Blix off to his remote castle. Blix ultimately escapes and becomes part of the next section which begins in the spring of 1793.

This is the story of Anna Stina, an even younger teenager who is taken into 'care' by the authorities when her mother dies. The house of correction is really a torture chamber. Girls are whipped to death for the amusement of their guards. Anna escapes and takes on the role of one of the girls who died, the daughter of an innkeeper. She is, however, already pregnant by the guard who helped her escape. It is then she meets Blix, who redeems his sins by doing her a favour. After Blix is lost Anna plans to change her appearance with acid. At this point the story catches up with itself and we are back on the edge of winter.

The story is incredibly dark. Stockholm is corrupt, debased, and stinks to high heaven. The author is himself a member of one of Sweden's oldest families, so we must assume he has access to all the insider knowledge.

Hard to believe, but The Wolf and the Watchman is a debut novel. And what a debut it is. Again, I can only compare it with the arrival in fiction of Umberto Eco.

The story itself is startlingly original. In Stockholm, in 1793, the one-armed watchman Mickel Cardell pulls a dead man from the water. I was originally going to say body but that is somewhat of an overstatement in the case of this man. His arms, legs, eyes, tongue and teeth have all been removed, in stages, before death. The under-pressure police chief summons his friend and sometime investigator Cecil Winge. Winge has solved potentially unsolvable cases before, and if he doesn't succeed this time, he has nothing to lose, given that he has already outlived expert estimates of death from consumption.

Cardell and Winge join forces, the former providing the physicality to the latter's brains. Of course they eventually find out the dead man's identity and who killed him, but not before the author has opened up the story in an amazingly bold way.

The story starts in Autumn 1793 but then goes backwards in time, first to the summer. This is the story of the teenaged surgeon's assistant Johan Kristofer Blix, who we are meant to assume is the mutilated victim. Blix falls foul of the wastrel elite and builds a substantial debt which is then sold on to a nobleman who carries Blix off to his remote castle. Blix ultimately escapes and becomes part of the next section which begins in the spring of 1793.

This is the story of Anna Stina, an even younger teenager who is taken into 'care' by the authorities when her mother dies. The house of correction is really a torture chamber. Girls are whipped to death for the amusement of their guards. Anna escapes and takes on the role of one of the girls who died, the daughter of an innkeeper. She is, however, already pregnant by the guard who helped her escape. It is then she meets Blix, who redeems his sins by doing her a favour. After Blix is lost Anna plans to change her appearance with acid. At this point the story catches up with itself and we are back on the edge of winter.

The story is incredibly dark. Stockholm is corrupt, debased, and stinks to high heaven. The author is himself a member of one of Sweden's oldest families, so we must assume he has access to all the insider knowledge.

Hard to believe, but The Wolf and the Watchman is a debut novel. And what a debut it is. Again, I can only compare it with the arrival in fiction of Umberto Eco.

Sunday, 29 September 2019

Tales From Hollywood - Christopher Hampton

This 1983 play is about the emigre German writers who found refuge from the Nazis in Hollywood: Brecht, for example, but mainly the Mann brothers, Thomas and Heinrich. Heinrich was the elder brother and was famous for his novels before Thomas but who was then eclipsed by his more conservative, deeper thinking sibling. By the time war breaks out both are in Hollywood but only Heinrich is reliant on Hollywood. Thomas tours universities and is tipped for the Nobel prize; Heinrich is spendthrift, bibulous and has a younger, lower-class wife, Nelly.

Our guide to this inversion of the Hollywood Dream is the Hungarian playwright Odon von Horvath, who is himself a dream in this story, given that he was killed by a falling tree in the Champs d'Elysees in 1938. But here he befriends Heinrich, pays reverence to Thomas, and responds a little too readily to Nelly's drunken flirting. The play ends badly for Nelly but not for Horvath, because he is already dead and finally, symbolically, realises it.

Hampton is one of the best writers of plays in English of the later Twentieth Century. In the Eighties it was basically between him and Stoppard, and after 1990 neither of them has written anywhere near enough. Both wear their book-learning as a badge of authority and neither has reflected deeply enough on the human condition, having both been successful from an early age. That does rather show in Tales From Hollywood.

What is it about? Displacement? Thomas Mann was permanently displaced; he wrote the bulk of his work outside Germany. Brecht wrote masterpieces like Galileo in exile and Heinrich's fame had already faded by 1940. Hovath, the child of an empire that had vanished during his lifetime, was a resident of nowhere - literally, in the context of the play. The only real displacement here is Nelly, who caught the roving eye of the man who thought up The Blue Angel and rose above her station. Tales of Hollywood is not about the writers who have no tales to tell about Hollywood, but about Nelly, who came to Hollywood with no dreams left and already out of place.

The famous writers are slightly two-dimensional, apart from our narrator, Hovath. He is a fantastic character and the best actors must yearn to play him: witty, self-deprecating, omniscient, playful, charming. And Nelly... a dream part, surely, for an actress just entering middle age. At the National Theatre in 1983 she was played by Billie Whitelaw. Casting that says it all.

Sunday, 22 September 2019

The Triumph of the Spider Monkey - Joyce Carol Oates

Hard Case Crime, my favourite brand of the moment, have really branched out. They now publish Stephen King and, that most literary of American writers, Joyce Carol Oates. I love Joyce Carol Oates and have done since I came across one of her earliest stories (pre-1973) in a collection from the Transatlantic Review..

What we have here is a novella from the same period, when Oates was still experimenting in authorial voice, and a shorter, linked novella from a couple of years later which has only ever been published in a literary journal.

The Spider Monkey is Bobbie Gotteson, abandoned as a new-born in a locker at the bus station. Bobbie is raised in care and detention centres, with the inevitable consequences. Upon release as a man of around thirty, but still looking young if a little monkeyish, he drifts out West with his guitar and vague dreams of becoming a star. Instead he turns into something not unlike Charles Manson, who was still on trial when Oates conceived the story.

It must be stressed, though, that Bobbie is not Charlie. He keeps his mystic powers to himself and his disciples are all in his head. But we know from the start that he is on trial for a series of murders. Among them is a houseful of air stewardesses, only one of whom has escaped. She is Dewaline, who features in the other novella, 'Love, Careless Love,' in which another footloose young drifter, Jules, is hired by persons unknown, to spy on her - for reasons unknown - as she attends to give evidence at Bobbie's trial.

Jules cannot resist approaching her. Dewaline assumes he is the driver hired (again, by persons unknown) to take her north after the trial. On the road, they become as involved as two alienated young people can be.

Oates is always worth reading. These early works are fascinating - experimental, multi-voiced, moving by jump-cuts like a post Easy Rider movie. Together, they are like reading a gonzo report from the frontline of the death of the Sixties dream.

What we have here is a novella from the same period, when Oates was still experimenting in authorial voice, and a shorter, linked novella from a couple of years later which has only ever been published in a literary journal.

The Spider Monkey is Bobbie Gotteson, abandoned as a new-born in a locker at the bus station. Bobbie is raised in care and detention centres, with the inevitable consequences. Upon release as a man of around thirty, but still looking young if a little monkeyish, he drifts out West with his guitar and vague dreams of becoming a star. Instead he turns into something not unlike Charles Manson, who was still on trial when Oates conceived the story.

It must be stressed, though, that Bobbie is not Charlie. He keeps his mystic powers to himself and his disciples are all in his head. But we know from the start that he is on trial for a series of murders. Among them is a houseful of air stewardesses, only one of whom has escaped. She is Dewaline, who features in the other novella, 'Love, Careless Love,' in which another footloose young drifter, Jules, is hired by persons unknown, to spy on her - for reasons unknown - as she attends to give evidence at Bobbie's trial.

Jules cannot resist approaching her. Dewaline assumes he is the driver hired (again, by persons unknown) to take her north after the trial. On the road, they become as involved as two alienated young people can be.

Oates is always worth reading. These early works are fascinating - experimental, multi-voiced, moving by jump-cuts like a post Easy Rider movie. Together, they are like reading a gonzo report from the frontline of the death of the Sixties dream.

Wednesday, 18 September 2019

Handsome Brute - Sean O'Connor

Probably the best researched book on sex killer Neville Heath, the 'handsome brute' of the title. Heath was brutish only in the way he treated the women he picked up in the transient world of London hotels in the immediate postwar period. He whipped them and he murdered two. But he was obviously debonair and charming - these women weren't idiots - and his wife in South Africa never accused him of violence. They divorced because he had married under a false name and was a convicted minor criminal.

O'Connor takes a critical view of his subject but doesn't really go into his mental state, issues raised at his trial, appeal, and in the Press. How deluded was he, if at all? That is and always was the question. He had a traumatic childhood with the death of a younger brother. He clearly had talent as a pilot and was undoubtedly brave in action. Because of his dishonesty he was court-martialed three times, yet did well in both the RAF and its South African equivalent. He was determined to serve. Was this heroism or a death wish? How do we differentiate between the two?

A book, therefore, that tells the tale thoroughly but leaves questions unanswered, which is not always a bad thing. Well worth looking out for.

(Great cover image BTW.)

Sunday, 15 September 2019

The Secret Rooms - Catherine Bailey

This is a captivating and unusual book. Bailey was granted access to the extensive archive of the Manners family, kept at Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire, home of the Duke of Rutland. Her aim was to research a book on the men of the Belvoir Estate during World War I. The current duke's great grandfather, Henry, had been a noted recruiter of volunteers for the Leicestershire Tigers. He had even offered to pay their usual wages while they were away.

On arrival she discovered the mystery of the secret rooms. This is where Henry's son John, the ninth duke had died in April 1940, aged only 53. More than that, he had locked himself in these humble 'business' rooms - excluding his family and some of the best doctors in the land - in order to work on the vast family archive. Moreover, it wasn't just the Manners papers that were stored there in 1940. The ninth duke had campaigned hard to ensure that huge chunks of the National Archive were secretly moved to Belvoir for safe keeping.

John himself had served in the First War. His father Henry had boasted that his own son - his only remaining son - was serving at the Front like the humblest farm hand. But Bailey soon discovered that the archives had been systematically edited - filleted by John - to remove all mention of certain periods in his life, including the latter part of his war service. Why? And who on Earth broke into the sealed rooms three nights after John's death?

As I say, it is a compelling story of arrogance, cowardice, bereavement and entitlement. Bailey builds the key characters as well as any novelist. Yet she is equally diligent in recording the problems of archival research. She answers the questions she set herself. Some solutions are sad, others downright extraordinary. She doesn't answer the one question I have always had about this truly ghastly family. How did they become dukes in the first place? They weren't warlords, nor royal by-blows. Sure, they owned and amassed inordinate land banks but so did many other families who came over with the Conqueror, and none of them became dukes. Other than pile up - and later lose - unimaginable fortunes, what did any of them ever do?

Thursday, 12 September 2019

Science Fiction Hall of Fame - the Novellas Book Two - (ed) Ben Bova

Another fascinating relic of Sixties and Seventies which I completely ignored at the time. Ben Bova's contribution is insignificant but the four novellas are all engrossing in their own way. Robert A Heinlein's Universe is on the hard side of sci-fi, set in a spaceship so big that is a world in itself, so far into its voyage that it has forgotten there is a universe outside. Vintage Season is by Henry Kuttner and his wife C L Moore (writing as Lawrence O'Donnell). Oliver takes in a family as vacantioners-cum-lodgers; they gradually reveal themselves as aliens on a visit to take in Earth before something happens. It would be crass to reveal what that something is, but it has to be said that the last line (which could easily be the first line of another story) is a stunner. The Ballad of Lost C'mell by Cordwainer Smith is the only novella here not written in the 1940s. It dates from 1962 and is pure Beatnik. It is extreme fantasy, set in a time when science has been sublimated, when "Earthport stood like an enormous wineglass, reaching from the magma to the high atmosphere." Jestocost is a Lord of Instrumentality whereas C'mell is a very girly girl, so girly that she is in fact a human-shaped cat, a homunculus. Yet Jestocost loves C'mell. The question is does she - can she - love him? And finally we have Jack Williamson's With Folded Hands, written in 1947 but still pertinent today because it is about the coming of the super-robots. The Prime Directive, a forerunner of Asimov's Laws, is brilliantly and bleakly enacted. It was for me the most effective novella in the collection, albeit Cordwainer Smith is a better writer.

Monday, 9 September 2019

Biggles Flies East - Captain W E Johns

Biggles Flies East (1935) is the seventh Biggles book, albeit Johns only started to publish them three years earlier. It is, like many of the early installments, a book for young adults rather than merely boys. The plot is complex and there are serious themes. The accurate historical detail, as always with Johns, is laid on good and thick. It is not, however, racist. The Huns are enemies, not crazed loons, and even the nomadic Arabs are portrayed as men of honour. They are, nonetheless, all men. I cannot recall a single female character, let alone a significant one.

Essentially, the plot is this: Biggles is seconded to Palestine where a man known as El Shereef is inciting the locals to rise up against the British. He is sent undercover to the Germans, posing as a British-born German pilot. Here he comes up against the man who is to become his enemy over the coming decades, Erich von Stalhein, whom he soon concludes is another spy. The British equivalent of von Stalhein is Major Sterne, who Biggles glimpses one night as a shadow in a tent.

Meanwhile Biggles's oppo Algy acts as his go-between with Military Intelligence. When Algy comes under fire from the German ace Leffens, Biggles has to save him. The dog-fight which follows is superbly done, genuinely exciting. The plot resolves neatly in the end and all loose ends are tied.

I haven't read Biggles since I was ten years old, though I hoped to dig my old copies out of the attic. Instead I found this brand new reprint by Red Fox on the carousel in my local library. I was very impressed.

Thursday, 5 September 2019

The Fatal Eggs - Mikhail Bulgakov

I love Bulgakov. He is my favourite writer and wrote my favourite book, The Master and Margarita. The Fatal Eggs (1924-5) isn't in that league, but it is seeded through with bits of Bulgakov at his best.

In 1928 (a 'future' four years after it was written) Professor Persikov invents a red ray that speeds up the reproductive process. His invention couldn't be more timely, because a plague has wiped out the poultry of several large provinces. Eggs are hurriedly imported and bathed in the crimson glow of Persikov's ray. Meanwhile the Professor returns to his zoological studies in which his specialism happens to be eggs. Unfortunately, due to a typical bureaucratic blooper, supplies of eggs get mixed up. Poultry farms receive the eggs of amphibians and reptiles while Persikov wonders what he's supposed to do with common or garden chicken eggs.

The outcome - for Bulgakov - is inevitable. Giant predatory reptiles run amok in the provinces and rioting Muscovites attack the scientists. It's all wild, comic and clever. Just as the common cold did for H G Wells' martians, so a premature frost polishes off the tropical monsters. But, being Bulgakov and not Wells, we are reminded that some poor wretches have to dispose of the rotting corpses.

A fine translation by Roger Cockrell perfectly captures the tone.

In 1928 (a 'future' four years after it was written) Professor Persikov invents a red ray that speeds up the reproductive process. His invention couldn't be more timely, because a plague has wiped out the poultry of several large provinces. Eggs are hurriedly imported and bathed in the crimson glow of Persikov's ray. Meanwhile the Professor returns to his zoological studies in which his specialism happens to be eggs. Unfortunately, due to a typical bureaucratic blooper, supplies of eggs get mixed up. Poultry farms receive the eggs of amphibians and reptiles while Persikov wonders what he's supposed to do with common or garden chicken eggs.

The outcome - for Bulgakov - is inevitable. Giant predatory reptiles run amok in the provinces and rioting Muscovites attack the scientists. It's all wild, comic and clever. Just as the common cold did for H G Wells' martians, so a premature frost polishes off the tropical monsters. But, being Bulgakov and not Wells, we are reminded that some poor wretches have to dispose of the rotting corpses.

A fine translation by Roger Cockrell perfectly captures the tone.

Tuesday, 3 September 2019

La Bete Humaine - Emile Zola

Zola's naturalism at its most extreme, humanity reduced to its most bestial. La Bete Humaine is really tough going. Everybody is determined to kill everyone else. Roubaud and Severine murder Grandmorin on the train between Paris and Le Havre. This takes place near the signal box run by Misard and the level crossing operated by his stepdaughter Flore. Misard is slowing poisoning his wife for her inheritance and Flore kills a dozen people because she is infatuated with her foster brother Jacques. Jacques's little problem is that he wants to murder every woman who excites him. He thinks that Severine has helped him over this minor difficulty and joins in her plan to murder her husband Roubaud. This is more than a tangled web. This is crazy. Yet Zola's gifts as a storyteller somehow carry the reader forward. It is one of those books you are going to finish, whether you like it or not. Personally, I'm not sure whether I like it. I certainly admire it. And I'm definitely glad I read it.

Thursday, 29 August 2019

SF The Best of the Best Part Two - ed. Judith Merril

Had to pick this up if only for the cover and the convoluted title. These mid-Sixties anthologies are notable for the oddments you find and how elastic they are willing to make the Sci Fi genre. The best story here, 'The Wonder Horse' by George Byram, has nothing whatever to do with either Sci Fi or fantasy. The premise is entirely about natural genes and it can hardly be a fantasy because every now and then a wonder horse does come along. I'm thinking Galileo and, currently, Enable. Byram captures the race fan's reaction perfectly. Indeed it is his immersion in the detail of the racing business that makes his story so good.

Similarly there's a Shirley Jackson oddment, "One Ordinary Day, With Peanuts", that just about scrapes in as fantasy, though I would be more inclined to call it a twisted tale. There's an early-to-middle period Brian Aldiss, "Let's Be Frank", which is simply a caprice, and there's the widely anthologised but nevertheless pure Sci Fi, J G Ballard's "The Sound Sweep", which I have discussed here before.

My favourites were "Nobody Bothers Gus" by Algis Budrys and "Day at the Beach" by Carol Emshwiller. Both well written, both leave as much to the imagination as they make explicit.

Thursday, 22 August 2019

February's Son - Alan Parks

I read Parks' first, Bloody January, in bloody January, which was apt. Damned if I was going to wait until next February to read the second in the Harry McCoy series, which is this, February's Son. It starts three weeks after Bloody January ended. McCoy has recovered from his injuries and is called into work the day before his sick leave was supposed to end. This being Glasgow in 1973, there has been a murder, a nasty one. The victim is the current star of Celtic FC and soon-to-be son-in-law of the murderous Jake Scobie, head of one of the Glasgow crime families. Has Jake heard that young Charlie has been playing away? It's a promising line of inquiry, but it grinds to a halt when Jake is butchered in just the same way.

Meanwhile McCoy's friend and childhood protector Stevie Cooper has seen a picture of one of their abusers, 'Uncle Kenny', in the paper. Now they know who Kenny is, can Cooper and McCoy let things lie? We all know that's unlikely.

As I said back in January, Parks is a real find, a direct heir to Ian Rankin, albeit they are about the same age. The police side of his stories is pure procedural with all the banter and implicit loyalties and feuds that involves. The noir side is very dark indeed. Everybody over the last decade has done a child abuse storyline, but Parks has his lead cop as a victim who carries his abuse with him for life.

February's Son is absolutely as good as Bloody January, maybe even slightly better. I like, for example, the way McCoy's relationship with Susan is handled, and the development of the role of Jumbo. The ending is again just a fraction contrived, but this is my one and only criticism. I loved it. Roll on March!

Tuesday, 20 August 2019

Trigger Mortis - Anthony Horowitz

I have got out of sequence with my post-Fleming Bond reboots. I have leapt from the first Gardner to one of the most recent. So what? Trigger Mortis is what I'd been hoping for, a Bond that is as great as the first three Connery movies. Horowitz, one of the most successful contemporary writers of general fiction, is a way better writer than Fleming, as indeed all Fleming's successors are. More importantly, he is a more gifted writer than any of the others, except perhaps Faulkes, who I haven't read. Most importantly, he has chosen to write in period, filling in the gaps, as it were. Trigger Mortis (the title sounds horrible but is in fact brilliant) comes immediately after Goldfinger. Thus we start off with Bond in bed with Pussy Galore. We then plunge headlong into Grand Prix racing at its most dashing and daring (the Nurburgring in 1957). This would have been good enough for many thriller writers but here is only Act One: it introduces the villain, a Korean meglamaniac, and the main plot, which is about the Space Race.

I am very cynical when it comes to Bond. I have already indicated the only movies I care about and it should be noted that I was only nine or ten when I fell asleep in the cinema during Thunderball. I have avoided anything that came after Roger Moore. I read all the Fleming books before I went to see Thunderball. I enjoyed them at the time, but was not a critical reader when only ten and under/ I revisited them perhaps fifteen years ago and was appalled at how bad they are. Fleming himself is interesting but nowhere near as interesting as his brother Peter, a real life adventurer, married to a movie star, and field commander of the British Resistance we never needed in the second World War. Peter was also a better writer, albeit he overwrites in the devil-may-care style popular in the Thirties when he wrote his bestsellers.

I therefore turned to those commissioned by the Estate to keep the cash rolling in. Colonel Sun and Licence to Kill are both reviewed on this blog. It's interesting that Gardner, who kept the franchise going longest, wrote a Moriarty version of Sherlock Holmes, as of course did Horowitz more recently. I preferred the Gardner Moriarity, which, coincidentally, I also read when I was both young and old. But I tell you, Gardner's Bond is not in the same league as Horowitz's. I genuinely cannot remember a thriller so well done, so thrilling that I could not stop reading.

An absolute triumph - a classic of its rather esoteric sub-genre.

Oh ... one last note. Trigger Mortis actually contains original material by Ian Fleming. Don't worry, it's not noticeable. Horowitz must have smartened up any actual writing, and it's only the writing that let Fleming down. The ideas were highly original, even brilliant in their day.

Saturday, 17 August 2019

London Rules - Mick Herron

The Jackson Lamb series really hits its stride with London Rules. The regular characters have been whittled down to the best, extraneous or one-off characters are kept in their place. The plot is excellent - a bunch of terrorists working through a destabilisation scheme stolen from MI5 - but Lamb novels are not about plot. No, the interplay of dysfunctional characters is what makes it work.

Take for example Roderick Ho. We don't care how good he is at computer stuff. We take his digital prowess as read. What matters to us is what a wazzock he is - and in London Rules he is the wazzock to end all wazzocks. Shirley Dander has been to compulsory anger management classes, which is like an arsonist stocking up on firelighters. And J K Coe is starting to emerge from his shell. All these are great ideas. Recent instalments have centred on River and Louisa; here they take more of a backseat. I personally enjoyed the reappearance of Molly Doran, the legless archivist of Regent's Park.

Excellent. I would say Herron is currently top of his genre. But the thought occurs, is he not the inventor and sole practitioner of this genre?

Take for example Roderick Ho. We don't care how good he is at computer stuff. We take his digital prowess as read. What matters to us is what a wazzock he is - and in London Rules he is the wazzock to end all wazzocks. Shirley Dander has been to compulsory anger management classes, which is like an arsonist stocking up on firelighters. And J K Coe is starting to emerge from his shell. All these are great ideas. Recent instalments have centred on River and Louisa; here they take more of a backseat. I personally enjoyed the reappearance of Molly Doran, the legless archivist of Regent's Park.

Excellent. I would say Herron is currently top of his genre. But the thought occurs, is he not the inventor and sole practitioner of this genre?

Tuesday, 13 August 2019

After the Silence - Jake Woodhouse

You wonder, how does a new writer get a four-book deal with Penguin? Then you read his personal profile. Then you realise what After the Silence actually means (the 1996 US movie, the charity that supports victims), And you realise, Woodhouse has confected a premise well nigh guaranteed to snag the attention of interns chasing hashtags at the publishers. He's an entrepreneur. He does wine. He has written a Euro thriller about child sexual abuse.

Of course, he would have got no further if he couldn't write or his book was boring. His writing is functional, which will do. His plot is well above average, bordering on very good indeed. But After the Silence is a moneymaker. Woodhouse even writes it in short filmic scenes to save the scriptwriter having to do it. There is no art here, nothing unexpected. The characters are given dense backstories but remain as dull as dishwater, and there are far too many protagonists.

Ostensibly Jaap Rykel of the Amsterdam police is our hero. His partner gets killed so obviously he wants to solve that but is not allowed to. Obviously he does it anyway. It doesn't take much solving, unfortunately; it is obvious who done it from the villain's first appearance. Jaap mainly has to solve the separate mystery of the dead man hanging naked from his apartment. His enquiries catch the attention of a young woman detective from the sticks who is investigating an arson murder of her own. And Jaap needs a new partner and has to make do with the one nobody else wants, whose various errors lead to more deaths.

It's all perfectly pleasant. I never wanted to stop reading but nor was I ever excited or intrigued. After the Silence is one of four, The Amsterdam Quartet, all of which are out now. I'm afraid I have got as far as I shall be going.

Wednesday, 7 August 2019

Murmuring Judges - David Hare

The second in David Hare's state of the nation trilogy, Murmuring Judges is, as the title suggests, an examination of the state of the legal system and what, in legal terms, counts as a win. The play was first staged in 1991 and it's disappointing how little has changed. Indeed - the question is unavoidable - can it change? In a combative system there can only be winners and losers, and one of the upsides of criminal law is that there are no grey areas. Having just written that last clause, I'm asking myself if it needs qualification. There should be no grey areas - you are either guilty or you are not. The intractable problem of the legal profession where everyone from beat constable to Lord Chief Justice keeps a scorecard is that grey areas are too often made out to be black or white.

Gerard gets five years, which seems a bit unfair. He was only a peripheral player in the crime and has no previous. But still his barrister, Sir Peter, can live with it. It was, after all, only a Legal Aid case. Not the sort of thing he would usually tackle. So Gerard is a new prisoner and Sir Peter has a new pupil, Irina. She's very bright, of course; she's also black and beautiful. She looks good on Sir Peter's arm for an evening at the opera. Trouble is, she's interested in Gerard's case. She recognises the unfairness of the sentence and is concerned about something the main police witness said.

The witness is Barry, who has a reputation for closing cases. His girlfriend Sandra is also concerned about Gerard's sentence. She was present on the arrests and noticed something odd in the way Barry treated the senior, more hardcore criminals.

The scale is panoramic - something that could only really be staged by a massive, publicly-funded theatre company. There are lots of characters and lots of subplots. You can almost see Hare plotting his thesis on a huge whiteboard. And it's very, very good. In the end Gerard wins his appeal and gets six months reduction in sentence. So everyone's a winner - except Lady Justice.

I had forgotten how good David Hare can be. I followed him when we were both young and still have most of his plays from those years. He went upmarket in the Eighties whereas I became much more political, and I ceased to pay attention. I have, however, seen his more recent TV films and found much to be enjoyed. Clearly I have catching up to do.

Tuesday, 6 August 2019

The Man Who Was George Smiley - Michael Jago

The title says it all. John le Carre admits basing his most famous character on John Bingham, his mentor during his brief time at MI5. Le Carre had to quit when his books became famous, Bingham didn't because the books he had been writing for over a decade had not been so successful. He was a noted author, nevertheless, and lots of people looked forward to the new Bingham novel in the Fifties. Unlike le Carre, Bingham didn't hide behind a pseudonym. Indeed, in his heyday, most people knew he was also Baron Clanmorris in the Irish peerage.

Bingham's ancestors are one of the fascinating elements of the book, especially his useless father Maurice and snobbish mother Leila, who spent much of their married life in seaside boarding houses. Bingham's own children were more successful - his daughter Charlotte was one of the scandalous young female authors of the Swinging Sixties, a big bestseller whilst still in her teens.

Bingham was something of an accidental intelligence officer. He was a newspaper columnist when war broke out and Maxwell Knight took him on. He quickly became Knight's deputy in the war against rightwing Nazi sympathisers in the UK. Knight left the service soon after the war but Bingham kept coming back, serving through the Cold War, the Blunt affair and the Troubles in Northern Ireland. He kept on writing but could not replicate his initial success or get anywhere near le Carre's fame. In truth, he will go down in history as the model for Smiley.

This is an unusual tack for a biographer to take and I must say Michael Jago pulls it off remarkably well. He is particularly good on the umbrage taken by Mrs Bingham/Lady Clanmorris, herself a published writer and performed playwright, who felt it was unfair that her husband's character should be hijacked with no recompense.

An excellent book, thoroughly researched and full of insights into the 'Circus' of the Sixties and Seventies.

Bingham's ancestors are one of the fascinating elements of the book, especially his useless father Maurice and snobbish mother Leila, who spent much of their married life in seaside boarding houses. Bingham's own children were more successful - his daughter Charlotte was one of the scandalous young female authors of the Swinging Sixties, a big bestseller whilst still in her teens.

Bingham was something of an accidental intelligence officer. He was a newspaper columnist when war broke out and Maxwell Knight took him on. He quickly became Knight's deputy in the war against rightwing Nazi sympathisers in the UK. Knight left the service soon after the war but Bingham kept coming back, serving through the Cold War, the Blunt affair and the Troubles in Northern Ireland. He kept on writing but could not replicate his initial success or get anywhere near le Carre's fame. In truth, he will go down in history as the model for Smiley.

This is an unusual tack for a biographer to take and I must say Michael Jago pulls it off remarkably well. He is particularly good on the umbrage taken by Mrs Bingham/Lady Clanmorris, herself a published writer and performed playwright, who felt it was unfair that her husband's character should be hijacked with no recompense.

An excellent book, thoroughly researched and full of insights into the 'Circus' of the Sixties and Seventies.

Friday, 2 August 2019

The Alchemist - Ben Jonson