Total Pageviews

Thursday, 29 May 2014

The Blackhouse - Peter May

The Blackhouse is the first novel in the Lewis Trilogy and May's breakthrough in the UK. But it's not his first novel - oh no, not by a long way. May has long been a bestseller in France, writing in French, with two long-running novel series to his credit, The Enzo Files and The China Thrillers. Yes, that's right, he writes about China in French. And is an honorary member of the Chinese CWA. The Blackhouse itself was originally written and published in French (L'Ile des Chasseurs D'Oiseaux) when no British publishing house would risk it. It won prizes in France, and no wonder. No wonder, by the way, that British publishing is at its lowest ebb, publishing ghost written drivel by 'celebs' and snubbing obvious classics of crime like this.

Having read the second of the sequence first (The Lewis Man) I thought I knew too much about what happened here (see my review below). But I was wrong. This is because of May's clever technique of going deep into his characters' past in the first person whilst driving the main plot in third. Thus, while I knew the punchline of The Blackhouse, I didn't know how that had come to be, and had no idea how central to the plot it was.

In many ways the French title is better. The key events, past and present, centre on the island where selected male islanders go once a year to club baby seabirds in a rite of passage. It's the perfect metaphor for the blend of deep, ancient tradition which young men like Fin Mcleod are eager to escape but never truly can. I enjoyed this book, indeed, even more than I enjoyed The Lewis Man. I will of course seek out the third novel, The Chess Men, but what I'm really looking forward to is the arrival, at last, of The Enzo Files, the first of which, Extraordinary People, is out now. The China Thrillers are available as ebooks. I'm in!

Tuesday, 27 May 2014

Selections from the Carmina Burana -David Parlett

This has become the classic modern translation. I don't know if it's accurate or not, because I don't speak medieval German and my Latin is so rusty it's effectively rotted away. As the title says, plainly enough, it's only a selection, but it's the best we've got, certainly in English.

Only tiny extracts of the original manuscript made into Orff's cantata and Parlett handily provides a section giving, effectively, the lyrics. Otherwise the text is sorted Sermons and Satires, Love and Nature, and Drinking and Gaming Songs. That last is the key - these are songs, always meant to sung or chanted aloud, probably to a musical accompaniment. The most famous of all, though it's hard to see why on this evidence, is the Archpoet's Confession, a slightly mocking mea culpa from a reprobate who isn't really sorry at all.

The Archpoet seems to have been referred to by that title in life, but that's pretty much all we know. He was almost certainly in the service of the Archbishop of Cologne who died in 1165. Nothing in the Carmina (which translates as the Songbook of Buren, a Benedictine monastery in Bavaria) is later than about 1230. So, for all its flaws and disappointments, it stands as an almost unique window on central European scholarly life in the age of Richard the Lionheart, whose magnificent mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, was an early sponsor of the Goliard tradition.

Parlett's notes are very good indeed.

Sunday, 25 May 2014

The Invention of Murder - Judith Flanders

Judith Flanders has produced a huge book, incredibly well-researched, but the subtitle for me indicates its main flaw. "How the Victorians revelled in Death and Destruction and created modern crime." Yes, true enough but not peculiar to the Victorians. The Elizabethans and the Georgians also revelled in true crime fact and fiction - consider Greene, Nashe, Fielding, and Defoe - and what really invented modern crime - that is to say, crime that is not entirely metropolitan - is mass transport, which admittedly came about during Victoria's reign although the steam train itself predates it.

Flanders, however, is a Victorian specialist and she knows her period in absolute detail. Not all the murders considered here are either gruesome or even interesting - Flanders' point is that they all, for one reason or another, caught the public imagination and were reinvented, sanitised or elaborated on stage or in fiction. She has made an exhaustive study of the yellow/gutter press, the 19th century equivalent of today's chip-paper/red-tops with their blithe disregard for truth.

For a thorough, single volume overview of British murder from the Red Barn to Jack the Ripper, The Invention of Murder would be hard to beat. Individual murders or murderers have been explored better elsewhere. What is absolutely invaluable for the murder buff, however, is the 40 page notes section. I found many leads for stories that especially interest me - and, to be absolutely fair to Flanders - not all of them were Victorian.

The Weeping Girl - Hakan Nesser

Book 8 of the Inspector Van Veeteren series is distinguished by not having Van Veeteren in it until the very end and then not in connection with the main storyline. I rather wish Nesser had found the resolve not to include him at all. It seemed forced.

Anyway, this is the Nesser novel I have liked best to date. I have always be fascinated by his odd fictional nowhere location that's a bit like Holland but isn't really. What has let down the series for me has been the involvement of too many detectives, which splinters the storyline. Here, Nesser takes the most interesting of Van Veeteren's former team - the only woman, Ewa Moreno - and takes her out of the usual Maardam setting by cleverly taking her on holiday, yet giving her credible police work to do by interviewing a supergrass in Lejnice, near her holiday spot. On the train she meets the weeping girl whose subsequent disappearance involves Ewa on the periphery of the official investigation while she independently opens up a monstrous can of worms involving a murder in the town sixteen years earlier.

By only having one investigator Nesser frees up the space necessary to fully explore that earlier murder and the circumstances which led to it. He held me enthralled - right up to the moment Van Veeteren stuck his nose in, when I would have reached for the editing tool.

There's a cracking review by Pam Norfolk, whose view differs from mine, here.

Thursday, 15 May 2014

Cockroaches - Jo Nesbo

The second Harry Hole thriller, originally published in 1998 but only translated into English last year. At last the UK publishing strategy becomes clear. They published Nesbo to cash in on Nordic Noir, following the huge success of Henning Mankell, but there was a problem with the Hole series - the first two, Cockroaches and the sub-standard Bat, are set in the very un-Scandinavian Thailand and Australia respectively. So they started with the Oslo-set Redbreast and stuck to the sequence until Nesbo was established as the most popular of all the Nordic crime writers.

Cockroaches is much better than the disappointing Bat. Nesbo really gets into his stride with the second outing for Harry. A Norwegian diplomat has been murdered in a seedy motel outside Bangkok. There are rumours of paedophilia. Send in Harry Hole, ostensibly because he made his name with the Australian case but really because--- As always with Nesbo's intricately crafted plots, it's easy to give too much away.

The characters are brilliant - the American female inspector of Thai police with alopecia, the ageing black ops agent, the financial whizz kid and the budding paralympian diver who flirts outrageously with Harry.

Forget episode one - this a series best started with episode two.

Tuesday, 13 May 2014

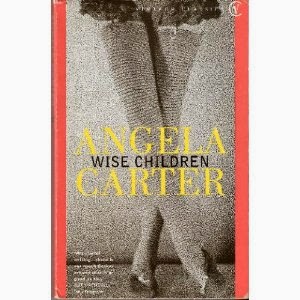

Wise Children - Angela Carter

Carter's last novel, published a year before her ridiculously early death, is a tour de force of wit and imagination. Dora and Nora are twin by-blows of the Hazard theatrical dynasty. On the day of their father's hundredth birthday (and that of his long lost twin), Dora sets down her memories of him/them and her and Nora's own career in illegitimate variety theatre. It's a novel about women but in no derogatory sense a 'women's' novel, any more than Charlotte Bronte or George Eliot are gender-limited authors. That said, Carter's feminist brio - both characteristics increasingly historical in the age of Katie Price - is what makes the story fizz and spark. The highlights are too numerous to mention. Come to think of it, I can't recall any lowlights whatsoever. A magnificent, truly beautiful book. What a loss Carter was.

Thursday, 8 May 2014

The Lewis Man - Peter May

The Lewis Man is the second of the Lewis Trilogy, following The Blackhouse and itself followed by The Chess Men. It has been hugely influential on Scottish crime fiction, as opposed to Tartan Noir. Let's face it, I have seen the story 'echoed' in Scottish TV crime series at least twice in the past two years. It is steeped in its setting. I assumed May was an islander but apparently he was born in Glasgow. I don't know how accurate his version of the Outer Hebrides is, but it is thoroughly convincing. He revels in the landscape and island history. History is what the story is all about - who is the peat bog man and what is his connection with Thormond Macdonald? Easiest thing would be to ask old Thormond, but he's got dementia ... which is the neatest twist in a multi-layered plot.

I especially enjoyed the way May took us inside Thormond's head, through first person narrative - his befuddlement with the present, and his crystal clear memory of the past. Our hero, ex-cop Fin Macleod, is treated in third person, which helps provide objectivity.

The Lewis Man is a fine piece of work, hotly recommended.

Sunday, 4 May 2014

George Passant - C P Snow

George Passant is the first of Snow's famous and now largely forgotten Strangers and Brothers sequence. Snow is a strange literary figure. His peerage was for work in the civil service and other public good but I remember as a child how highly regarded his writings were. He died around the time I wouldn't read a roman fleuve with a gun to my head and has never really returned to the public consciousness.

That said, I really enjoyed this book. OK, it took a while to get going and the habit of anonymising Leicester as 'the town' while referring to the immediately surrounding area as Leicestershire was a minor annoyance throughout. But once I got hold of the tone I couldn't tear myself away. The narrator, Lewis Eliot, is largely characterless, an onlooker to the point where Passant's life starts to unravel. Then what we have is a young man (Eliot) coming to terms with the shortcomings of his mentor (Passant), who in turn is brought down, in part, by the shortcomings of his mentor, the eccentric solicitor Martineau (of my favourite thoroughfare, New Walk).

The story begins in 1925 with the slightly older Passant creating a group of young acolytes who enjoy free-thinking weekends (and, we discover later, free-loving) at a local farmhouse. Over the years the originals like Eliot and Jack make their own way and Passant rather lags behind. Then he goes into business with Jack...

The period detail was fascinating, as was the blend of new and old. Snow's writing style is not great - far too much use of the colon for my liking, and truly horrible chapter headings. But he has the soul of a novelist and the mind of a great one. There's nothing for it - I shall have to read more.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)