Total Pageviews

Thursday, 31 October 2019

The Streets - Anthony Quinn

London, 1882. David Wildeblood is the new Somers Town correspondent of Henry Marchmont's campaigning newspaper The Labouring Classes of London, a post secured for him (after some personal difficulties) by the godfather he has never met, Sir Martin Elder. Somers Town, for those who do not know, is the site of the future Euston Station. In 1882 it was a warren of decaying housing, a slum but not quite a Dickensian rookery. It is an alien world to the naive young David but he finds a guide, the market trader Jo. He also finds that the local vestry - equivalent, more or less, of a parish council - is comprised of dodgy landlords who actually own the slums, for which they charge extortionate rents. This leads the bold investigator to a larger, more sinister conspiracy, involving forced evacuation of the poor and even eugenics.

The initial premise, the corrupt vestry, was familiar to me, probably from the real-life work of Mayhew and Booth, both of whom Quinn acknowledges as sources,* but where the author then went with it was fresh and startling. Quinn makes his point, which is not a million miles away from the subtext of the Cameron-Clegg coalition in 2012, when he wrote it, without ever cutting back on the literary quality. Quinn is a very fine novelist indeed. Not many contemporary novelists could get away with 'refulgent' but Quinn does, twice.

More important, of course, are his characters, all beautifully brought to life in three dimensions. I was extremely impressed.

* Since writing the above I have remembered where I saw it - Sarah Wise's The Blackest Streets, which is also credited by Quinn and reviewed on this blog.

Sunday, 27 October 2019

The Border - Don Winslow

Winslow - back on top form. Brilliant.

The Border concludes the Cartel trilogy and brings it bang up to date. Art Keller emerges from the Guatemalan jungle to take over as head of the DEA, having realised that the only way to tackle America's drug problem is to take out the big money men. That doesn't just mean the Cartel bosses, because Keller now knows there are people above them on the US end of the chain. For the Cartels drugs mean money and power. For the financiers power can be bought by money. And now they plan to buy the ultimate power.

Meanwhile, the fact that Keller has finally taken out Adan Barrera, head of the Sinaloan Cartel and effective boss of bosses, means that the second tier go to war to determine a successor. The lack of order means there are vacuums for figures from the past to return to: men like Rafael Caro, who tortured and murdered Keller's partner thirty years ago, and Eddie Ruiz who was there when Keller took out Adan.

It is a big, BIG story, and rightly so. In so many ways it is the story of our time, the fifty year war on drugs which America has not and will never win. How close Winslow's fiction comes to reality will be open to debate. What is inarguable, a stone fact, is that nobody does this story better than Don Winslow. Does anybody else even dare to try? Each of the three novels - The Power of the Dog, The Cartel, and now The Border - is a major achievement. The three together are a landmark.

Monday, 21 October 2019

Laura - Vera Caspary

Laura was Caspary's break into the big time. It came out in 1943, having previously been serialised in a magazine, became a Otto Preminger movie in 1944 and a stage play the year after. It is a hard-boiled crime of passion novel with all the qualities of the best literary fiction.

Waldo Lydecker is a New York writer of literary fiction. He is fat, snobbish and affected, with a silly beard and an ebony cane. He is our first story-teller, for Caspary has emulated the Moonstone device of multiple first-person narration. Lydecker is besotted with Laura, as is every man she ever met. Lydecker was seeking to introduce her to art and society, so when she is found dead in her apartment, shot in the bewitching face, Lydecker is the second person Detective Mark McPherson calls on, after Laura's fiance, Shelby Carpenter. Laura and Shelby were due to be married the next week. She had planned a final solo holiday but before she left was due to dine with Lydecker.

The plot is astonishing. My jaw genuinely dropped at the big twist. Caspary drip-feeds the clues like a research scientist breeding bacteria. Everything you need to know is there, none of it apparent without hindsight. The novel is short, exquisitely so, but every word is loaded with meaning. And the style, like the cover art on this Vintage edition, is superb. The following is from Detective McPherson, the fish out of water in the refined circle inhabited by Lydecker, Laura and Carpenter:

Even professionally I've never been inside a night club with leopard-skin covers on the chairs. When these people want to insult one another, they say darling, and when they get affectionate they throw around words that a Jefferson Market bailiff wouldn't use to a pimp. [...] It takes a college education to teach a man that he can put on paper what he used to write on a fence.

Thursday, 17 October 2019

In a House of Lies - Ian Rankin

The odd dud is inevitable when you are as prolific as Ian Rankin, and this is undoubtedly one of his. It seems to be based on two celebrated podcasts about murder, the Adnan Syed case which made Serial a worldwide hit and the murder of Daniel Morgan in London in 1987. Basically we have the murder of a private detective and the key clue about how long a car was parked where it was found which hinges on the analysis of soil and grass. Note to Rankin: You're a crime writer; never assume your crime readers are less informed than you are.

The second problem is that Rankin continues to employ the detective triad which, for me at least, is no longer interesting or indeed credible: Rebus, Malcolm Fox and Siobhan Clarke. It is essentially a good idea. Now he is retired Rebus can be even more of a wild card; Clarke has to obey the rules or her long association with Rebus will hold her back; and Fox polices the police. The problem is, they all come with baggage from up to 21 previous outings, or, in Fox's case, from two novels in which he was the replacement for Rebus. This means a certain number of secondary characters have to revisited, even if there is no plotting need. If Rankin isn't at the very top of his game, this can lead to an imbalance between investigation and back story. Needless to say, in Rebus #22, Rankin isn't at the apex of his ability.

It's readable - Rankin is always readable - but the problems are overwhelming. Both the A plot and the B subplot are fundamentally unbelievable; no one kills or accepts the blame for killing for such trivial reasons. And the novel itself is about 25% too long. I hope Rankin recovers form for the next Rebus. I for one could not take another misfire, especially as recent instalments have been so good.

Monday, 14 October 2019

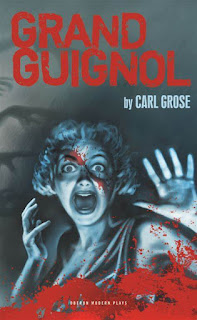

Grand Guignol - Carl Grose

Grand Guignol is a play. Not a Grand Guignol play but a play about Grand Guignol, specifically the creation of the form in the Parisian theatre of that name around 1900. It starts with a performance of such a play which causes the celebrated physiologist Alfred Binet, the inventor of intelligence testing, to intervene. He simply cannot contain himself and leaps up onstage, breaking the illusion. He gets introduced to the Prince of Terror, Andre de Lorde, otherwise a shy, unassuming librarian and they start to collaborate. Ultimately they conceive the most outrageous of classic Grand Guignol (certainly in England), Crime in a Madhouse.

The performance switches between actual performance and the actors who are doing the performance. Everything we need to know about Grand Guignol in order to follow the action is provided. It is more or less accurate - Grose in his acknowledgements cites the best known authorities on the form, Mel Gordon, Richard Hand and Michael Wilson. There is what I felt was an unnecessary subplot and one rather clumsy in-joke. Other than that, the play is great fun and I would love to see it live.

Grand Guignol was first performed in The Drum at the Theatre Royal Plymouth on October 29 2009.

Tuesday, 8 October 2019

Goldstein - Volker Kutscher

Goldstein is the third of the Gereon Rath novels, not to be confused with the forthcoming third series of the Babylon Berlin TV series, to which the only resemblance is the appearance of Gereon Rath and the Weimar Republic.

The titular Goldstein is an American mob assassin of German Jewish heritage, who pitches up in Berlin in 1931. Rath, having blotted his copybook once more, is given the job of tailing him. Meanwhile someone is killing proto-Nazis, including cops, and Rath is specifically excluded from the investigation - which, of course, means he solves it.

Kutscher's series has been an international hit, in print and more so on TV, the latter because it contains a great deal of sexual material which is absent from the books. The fact remains, though, that Kutscher is not making the techical development he should be. Goldstein is by far the most interesting character here, but disappears for most of it. Rath's sideline working for the gangster Johann Marlow is this time little more than perfunctory.

The book starts off great, with two teenage burglars robbing a major store, but rapidly goes flabby. I enjoyed The Silent Death more than Babylon Berlin but I enjoyed both of them more than I enjoyed Goldstein. Not a good sign for the future.

Tuesday, 1 October 2019

The Wolf and the Watchman - Niklas Natt och Dag

An extraordinary achievement, fully deserving all the hype it has received, The Wolf and the Watchman is certainly the historical novel of the year, possibly the best since The Name of the Rose, back in the Eighties.

The story itself is startlingly original. In Stockholm, in 1793, the one-armed watchman Mickel Cardell pulls a dead man from the water. I was originally going to say body but that is somewhat of an overstatement in the case of this man. His arms, legs, eyes, tongue and teeth have all been removed, in stages, before death. The under-pressure police chief summons his friend and sometime investigator Cecil Winge. Winge has solved potentially unsolvable cases before, and if he doesn't succeed this time, he has nothing to lose, given that he has already outlived expert estimates of death from consumption.

Cardell and Winge join forces, the former providing the physicality to the latter's brains. Of course they eventually find out the dead man's identity and who killed him, but not before the author has opened up the story in an amazingly bold way.

The story starts in Autumn 1793 but then goes backwards in time, first to the summer. This is the story of the teenaged surgeon's assistant Johan Kristofer Blix, who we are meant to assume is the mutilated victim. Blix falls foul of the wastrel elite and builds a substantial debt which is then sold on to a nobleman who carries Blix off to his remote castle. Blix ultimately escapes and becomes part of the next section which begins in the spring of 1793.

This is the story of Anna Stina, an even younger teenager who is taken into 'care' by the authorities when her mother dies. The house of correction is really a torture chamber. Girls are whipped to death for the amusement of their guards. Anna escapes and takes on the role of one of the girls who died, the daughter of an innkeeper. She is, however, already pregnant by the guard who helped her escape. It is then she meets Blix, who redeems his sins by doing her a favour. After Blix is lost Anna plans to change her appearance with acid. At this point the story catches up with itself and we are back on the edge of winter.

The story is incredibly dark. Stockholm is corrupt, debased, and stinks to high heaven. The author is himself a member of one of Sweden's oldest families, so we must assume he has access to all the insider knowledge.

Hard to believe, but The Wolf and the Watchman is a debut novel. And what a debut it is. Again, I can only compare it with the arrival in fiction of Umberto Eco.

The story itself is startlingly original. In Stockholm, in 1793, the one-armed watchman Mickel Cardell pulls a dead man from the water. I was originally going to say body but that is somewhat of an overstatement in the case of this man. His arms, legs, eyes, tongue and teeth have all been removed, in stages, before death. The under-pressure police chief summons his friend and sometime investigator Cecil Winge. Winge has solved potentially unsolvable cases before, and if he doesn't succeed this time, he has nothing to lose, given that he has already outlived expert estimates of death from consumption.

Cardell and Winge join forces, the former providing the physicality to the latter's brains. Of course they eventually find out the dead man's identity and who killed him, but not before the author has opened up the story in an amazingly bold way.

The story starts in Autumn 1793 but then goes backwards in time, first to the summer. This is the story of the teenaged surgeon's assistant Johan Kristofer Blix, who we are meant to assume is the mutilated victim. Blix falls foul of the wastrel elite and builds a substantial debt which is then sold on to a nobleman who carries Blix off to his remote castle. Blix ultimately escapes and becomes part of the next section which begins in the spring of 1793.

This is the story of Anna Stina, an even younger teenager who is taken into 'care' by the authorities when her mother dies. The house of correction is really a torture chamber. Girls are whipped to death for the amusement of their guards. Anna escapes and takes on the role of one of the girls who died, the daughter of an innkeeper. She is, however, already pregnant by the guard who helped her escape. It is then she meets Blix, who redeems his sins by doing her a favour. After Blix is lost Anna plans to change her appearance with acid. At this point the story catches up with itself and we are back on the edge of winter.

The story is incredibly dark. Stockholm is corrupt, debased, and stinks to high heaven. The author is himself a member of one of Sweden's oldest families, so we must assume he has access to all the insider knowledge.

Hard to believe, but The Wolf and the Watchman is a debut novel. And what a debut it is. Again, I can only compare it with the arrival in fiction of Umberto Eco.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)