With sci fi, your premise is everything. Fritz Leiber (1910-1992) is an acknowledged master of the genre whose series morphed into fantasy games, so you would think he knew all about premises. Gather, Darkness (1950) was his second novel and the premise seems strong but ends up as basically fatuous.

As a young man Leiber studied as a candidate minister in the episcopal church and that may well be where he got the idea for the priestly Hierarchy which rules the world in the Second Atomic Age. The Hierarchy is, it goes without saying, oppressive and tyrannical. Commoners are kept in serfdom, tithed, and subject to curfew. The resistance, as it were, is the Witchcraft. They are not what one might call active in their resistance to begin with, but then Brother Jarles, priest of the First and Outermost Circle, goes rogue and reveals the great truth of the Hierarchy to the common people - that priests do not believe in God. Sadly, the Witchcraft don't believe in the Devil either. That is a pity because old Mother Jujy really is a witch.

The Witchcraft, however, do keep familiars - little vampiric versions of themselves - and these are great fun. There is a leader called Asmodeus but I'm not entirely sure if he is real or not. Anyway, the Witchcraft try and recruit Jarles, who refuses. He is recaptured and brainwashed by the Hierarchy and then promoted to the Fourth Circle. Leading priest and subsequent dictator Goniface sees something in him. He reminds the great man of his youthful self, when he too believed in fairness and honesty. All a long way behind him now, of course. But the sister he chucked off a bridge when she threatened his career... she seems to be still about and utterly un-aged. Surely she is the beautiful young witch and weaver Naurya, who Jarles is infatuated with.

Anyway there's a rising. This leads to civil war. Gondiface surrenders even though he is winning. It's all very complicated. It has its entertaining moments but, overall, the passage of time has done for poor old Leiber. The hi-tech visual equipment he postulates is less futuristic than a 1960s portable TV. There are no computers. Messages are delivered by runner. And, for me, it's all just a bit too po-faced. Interesting, though.

Total Pageviews

Thursday, 31 May 2018

Saturday, 26 May 2018

Munich - Robert Harris

The blurb on the back, from The Times, describes Harris as "Master of the intelligent thriller". You can't argue with that. In three successive standalone novels - An Officer and a Spy, Conclave and now Munich - he takes storylines you already know the end of (or don't care in the case of Conclave) - and somehow, inexplicably, makes them exciting. I say 'inexplicable' but it must be possible to work out how he does it. I must take the time, sometime.

Here, obviously, this is the Munich Crisis of 1938. We all know how that turned out. Chamberlain waving his bit of paper at Croydon airport; 'Peace in our time. Part of how Harris makes this work so well is his unexpected sympathy for Chamberlain, until David Cameron came along, surely the most despised British Prime Minister of the media age. Harris, we recall, did a variant of this in The Ghost, wherein his unforeseen contempt for the clone of his old friend Tony Blair was the only saving grace of (for me) an execrable book. The other device that works very well in Munich is the use of two protagonists, Hugh Legat and Paul Hartmann, former Oxford friends who now attend the last-minute 'peace' conference as rising stars of the their respective civil services. How they will come out of it, particularly Paul who is most at risk, provides both the tension and a breathtaking twist right at the end which I for one never saw coming.

Thus a great deal of artistry goes into the construction of Harris's story which hides comfortably behind his seemingly effortless and efficient prose. The Times is right. There's only one word for Munich, that's masterly.

Wednesday, 23 May 2018

Behold the Man - Michael Moorcock

Moorcock is the king of modern British sci fi. He has been writing at a stupendous rate for more than fifty years and there are more than a hundred books. This, from the late Sixties and Moorcock's late twenties, is one of very few stand alone works. A version - a novella version - of Behold the Man won the Nebula award (best novella 1967). The thing about Moorcock is, he constantly reworks, rewrites and expands. There are multiple versions of various stories, just as there are multiple universes in some of his fiction.

This, it might be said, is Moorcock's distinctive take on H G Wells' The Time Machine. Wells, being Wells, was only really interested in the future. The time machine here, we are told as soon as our hero sees it, cannot go forward, only back. And if we can only go back - subject to the usual caveat of not changing history - where would most of us choose to go? Elizabethan England perhaps? The age of the dinosaurs? The Holy Land circa 30AD? As might be guessed from the title, our hero Karl Glogauer opts for the latter.

His life in Sixties London, which is recreated throughout the novel, has led him to question his religious beliefs. So when the physicist Sir James Headington shows him his time machine and invites him to use it, Karl has only one destination in mind.

Virtually the first person he encounters in Roman Palestine is John the Baptist. Fortunately Glogauer has taught himself Aramaic, unfortunately John doesn't seem to have heard of his supposed cousin, Jesus of Nazareth. Yet the time is right - 28AD. Jesus should be mustering disciples and spreading the Word. His ministry won't last long and, critically, John has to die first.

Thus begins Karl's quest for the as yet unknown Nazarene. I won't reveal how it pans out but will just state that it does so in a highly satisfactory manner.

This is the first full-length Moorcock I have tackled. I was put off about the time he was writing the original version of Behold the Man, by a ridiculous piece of fluff he wrote for an alternative magazine of Swinging London. I enjoyed this hugely. I loved the nonstop tide of ideas, the clever way he play with the various levels of narrative and the distinctive tone he gives to each. Glogauer is an amiable hero, not quite an everyman, more an everyday avatar of the polymathic Moorcock. I have already ordered another Moorcock - one which isn't listed among the hundred or so in this series from Gollancz but which Moorcock himself mentions in his introduction - called Mother London. I am definitely keen to read his take on Elizabeth I, Gloriana, though I am slightly worried that has something to do with the off-putting bilge I read on the train home from London circa 1968-9. We'll see.

This, it might be said, is Moorcock's distinctive take on H G Wells' The Time Machine. Wells, being Wells, was only really interested in the future. The time machine here, we are told as soon as our hero sees it, cannot go forward, only back. And if we can only go back - subject to the usual caveat of not changing history - where would most of us choose to go? Elizabethan England perhaps? The age of the dinosaurs? The Holy Land circa 30AD? As might be guessed from the title, our hero Karl Glogauer opts for the latter.

His life in Sixties London, which is recreated throughout the novel, has led him to question his religious beliefs. So when the physicist Sir James Headington shows him his time machine and invites him to use it, Karl has only one destination in mind.

Virtually the first person he encounters in Roman Palestine is John the Baptist. Fortunately Glogauer has taught himself Aramaic, unfortunately John doesn't seem to have heard of his supposed cousin, Jesus of Nazareth. Yet the time is right - 28AD. Jesus should be mustering disciples and spreading the Word. His ministry won't last long and, critically, John has to die first.

Thus begins Karl's quest for the as yet unknown Nazarene. I won't reveal how it pans out but will just state that it does so in a highly satisfactory manner.

This is the first full-length Moorcock I have tackled. I was put off about the time he was writing the original version of Behold the Man, by a ridiculous piece of fluff he wrote for an alternative magazine of Swinging London. I enjoyed this hugely. I loved the nonstop tide of ideas, the clever way he play with the various levels of narrative and the distinctive tone he gives to each. Glogauer is an amiable hero, not quite an everyman, more an everyday avatar of the polymathic Moorcock. I have already ordered another Moorcock - one which isn't listed among the hundred or so in this series from Gollancz but which Moorcock himself mentions in his introduction - called Mother London. I am definitely keen to read his take on Elizabeth I, Gloriana, though I am slightly worried that has something to do with the off-putting bilge I read on the train home from London circa 1968-9. We'll see.

Monday, 21 May 2018

Bloodline - Mark Billingham

Hard to say where Bloodline fits into the Tom Thorne series. I suspect it is Number 8. Does it matter? Not really. Bloodlines is still the right side of the dividing line which threatens all series - it is a crime thriller with bits of character development thrown in, rather than a character novel with bits of crime bolted on. In fact Billingham handles the 'personal life' stuff very well here. There is a major domestic crisis which reflects the main crime theme but the character development is that both Thorne and his partner Lou bury their feelings in their police work and prioritise the crime.

It is a serial killer story because Billingham is essentially a writer of very dark noir. The question is, in an era where genetic research is everything, can serial killing be an inherited trait? Essentially, the supposed son of a famous serial killing is going round killing the children of his father's victims in order to 'prove' that his father was obeying genetic code rather than personal inclination. It's a great idea, handled well on the whole, though I would have preferred some deeper development. Billingham rather handicaps himself in that respect by sending super-pathologist Hendricks, the fount of all theoretical argument in Thorne's world, to a conference in Sweden.

My only other reservations are these: I didn't care for the tricksy prologue and quickly fathomed out its relevance; and I really didn't like the killer's journal. These are very minor quibbles. I'm sure other people thought they were great. Yes I guessed who dunnit as soon as we were introduced but that to me is no problem at all. The plotting was as ever fiendish and Billingham writes like a well-modulated dream. The dialogue crackles, especially the banter between Thorne and Hendricks.

Has Billingham succeeded Rankin as the premier UK crime writer of today or is that Val McDermid? It's a close one and I fancy it boils down to how quickly Rankin dumps the increasingly tedious Malcolm Fox and fully revivifies Rebus.

Thursday, 17 May 2018

The Encyclopedia of the Dead - Danilo Kis

Danilo Kis (1935-1989) was a Yugoslavian expat, living and working in France. He wrote some novels but is perhaps better remembered for his short stories (or pocket-sized novels, as he called them) of which this, from 1983, was his final collection.

Kis's style deliberately reminds us of Borges but I also found links with Umberto Eco (whose Prague Cemetary is strongly reminiscent of Kis's 'The Book of King and Fools') and Isak Dinesen (very much so in an off-beam love story like 'Last Respects'). He is elusive and goes to considerable lengths to disguise fiction as fact. The key story here is presumably 'The Encylcopedia of the Dead' itself, which is what it says it is - a woman looks up her father in the huge encyclopedia of everyone who has not been recorded elsewhere. Actually I wanted the story to go further - so that should you ever be mentioned in any other written record (such as a short story or a memoir) you are automatically deleted from the encyclopedia of unknowns. Perhaps that is easier to envisage in the age of the internet. Kis's story is an uncomfortable reminder how far archival records have come in just 35 years. I liked 'The Book of Kings and Fools' even more, largely because I had read and enjoyed Prague Cemetery so recently.

My favourite over all, though, is 'Simon Magus', the gnostic story of the rival messiah who fell spectacularly foul of Christ's disciples. This is exactly the sort of story I love to read and write.

I am not the biggest fan of introductions. Here, however, the introduction is by Mark Thompson, who is Kis's biographer, and I feel the stories would have been harder to get into without it.

Kis's style deliberately reminds us of Borges but I also found links with Umberto Eco (whose Prague Cemetary is strongly reminiscent of Kis's 'The Book of King and Fools') and Isak Dinesen (very much so in an off-beam love story like 'Last Respects'). He is elusive and goes to considerable lengths to disguise fiction as fact. The key story here is presumably 'The Encylcopedia of the Dead' itself, which is what it says it is - a woman looks up her father in the huge encyclopedia of everyone who has not been recorded elsewhere. Actually I wanted the story to go further - so that should you ever be mentioned in any other written record (such as a short story or a memoir) you are automatically deleted from the encyclopedia of unknowns. Perhaps that is easier to envisage in the age of the internet. Kis's story is an uncomfortable reminder how far archival records have come in just 35 years. I liked 'The Book of Kings and Fools' even more, largely because I had read and enjoyed Prague Cemetery so recently.

My favourite over all, though, is 'Simon Magus', the gnostic story of the rival messiah who fell spectacularly foul of Christ's disciples. This is exactly the sort of story I love to read and write.

I am not the biggest fan of introductions. Here, however, the introduction is by Mark Thompson, who is Kis's biographer, and I feel the stories would have been harder to get into without it.

Tuesday, 15 May 2018

Blood Brothers - Ernst Haffner

Blood Brothers was published in Germany in 1932 and suppressed the next year. It was rediscovered and republished in Germany in 2013. That's it - all we know. It's a lot more than we know about Haffner, whom we are told was a journalist and social worker. Blood Brothers is his only novel, his only book. He disappeared sometime between 1932 and 1945. There is not even a photograph of him.

What a legacy this is. It's always difficult with translations to know how accurately they reflect the original text. But Michael Hofmann is the virtuoso of translators from the German. So we can be confident that his translation is accurate and faithful. Therefore Haffner himself wrote in these breathless, staccato sentences, some of them not even complete sentences. Simplistic as they may seem, the sentences are loaded with meaning. They go off like firecrackers.

What we have is a novel of lost boys, boys in their teens who have run away from boys' homes and subsist by crime on the dark streets of Berlin. They are a gang, they share a situation, yet each is sharply defined and differentiated. We have the charismatic leader, Jonny. You can always count on Jonny. We have Fred, more flamboyant, who is the gang treasurer. And then there's Ludwig, picked up for another man's crime, who is taken back into care, only to escape again with Willi, who - paradoxically - helps him go straight in the refurbished boot business. The gang breaks up, inevitably, as the lads move on or are gaoled. It doesn't matter. They know this was always going to be a sunny interlude amid a gathering storm. Berlin can manage without them because there will always be others. There is only one Berlin. Berlin is the star, the protagonist of the superb Blood Brothers.

Thursday, 10 May 2018

1Q84 Book One - Haruki Murakami

I do so many things backwards. Reading 1Q84 was one such. I read it out of sequence. I knew how it ended before I knew how it began. It made no difference whatsoever. I enjoyed every second of it and discovering 1Q84 introduced me to Murakami's other work, of which I have now read a good deal.

Here we get everything we need to know about Tengo, Aomame and, perhaps most importantly, Fuka-Eri, the seventeen year old genius behind Air Chrysalis and the Sakigake cult from which she has escaped. It's an interesting link - Aomame left the Witnesses at about the same age. Akebono, which I don't remember from the later books, was a militant sub-sect of Sakigake, and their shootout with the police (very 1980s) is why the police (in 1Q84) are armed. This is the first discrepancy which Aomame notices when she crosses into the parallel world. Tengo doesn't actually cross over in this first book. We learn the full details of the very tenuous connection between our two protagonists and - for what I suspect is the one and only time - why the book is called 1Q84. Aomame comes up with the name to reinforce the idea that she is no longer in her 'real' 1984; whatever this is, it isn't that, so the Q stands for question mark. I can't even imagine how this worked in the original Japanese.

The style - leisurely, straightforward prose rolling gently out - is there to smooth the edges of the ideas which are often incredibly complex. I feel sure we get most if not all of Murakami's world view across the trilogy, but it so gently, so persuasively done that nothing jars, nothing seems at all unacceptable. For example, we see what Aomame does for a living right at the beginning of the book. We are later given suggestions why she does it. In lesser hands it would repel us or at least warn us we are tackling a noir world. But here it doesn't repel. Here the two-moon world is far from noir.

1Q84 is what it was instantly recognised as being - a classic of world literature. That's a beautiful thing.

Tuesday, 8 May 2018

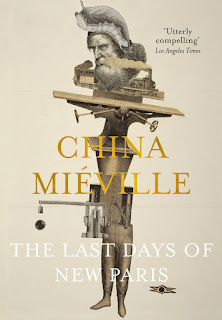

The Last Days of New Paris - China Mieville

The Last Days of New Paris is a novella, and better for it. The other Mieville novel I have read (Kraken, which I reviewed here last year) went on just that bit too long. Here, the ideas are fizzing throughout but the tighter narrative seems to help Mieville maintain the high standard of his prose.

The idea itself is a corker. Surrealist concepts are brought to life in Nazi-occupied Paris. As a result Paris is still occupied - indeed, cordoned off from the rest of the world, with the rest of the world's blessing - in 1950. These manifestations ('manifs') are predominantly on the side of the resistance (specifically the Surrealist resistance, the Main a plume) of which our hero Thibaut is a member. Thibaut wears one manif, the armour of Surrealist women's pyjamas, and joins forces with another, the Exquisite Corpse (featured on the cover) dreamt up by Breton, Lamba and Tanguy. The Nazis created the manifs with the S (for Surrealist) bomb, the creation of which in 1941 is the secondary storyline here, but the manifs naturally hate them for it. The Nazis have therefore done a deal with Hell and signed up hellish demonic monsters. Also involved is Sam, an American woman photographer, who may or may not be with the OSS, forerunner of the CIA. She is collecting photographs for a book called - typically Mieville - The Last Days of New Paris.

I enjoyed this hugely. It is precisely my cup of tea, right down to the account of how Mieville came by the story and the learned notes at the end. Just reading it inspired me. Hopefully it will do the same for you - because you have to read it.

Labels:

Andre Breton,

China Mieville,

Exquisite Corpse,

fantasy,

Jacqueline Lamba,

Kraken,

Last Days of New Paris,

main a plume,

manif,

Nazism,

novella,

Paris,

sci fi,

steampunk,

Surrealism,

Yves Tanguy

Friday, 4 May 2018

Drama City - George Pelecanos

Drama City (2005) is one of Pelecanos's slice of life stories, set on the dark side of Washington DC. The title is meant to be a play on the two drama masks, comedy and tragedy, but there is no comedy here. It's all tragedy and, as in the classical model, it is all inevitable. It is inevitable that Lorenzo Brown, ex-con going straight as dog police with the Humane Society, gets drawn back to his criminal past. It is inevitable that Rachel Lopez, his probation officer, pays the price for either her free and easy sex life or her commitment to her clients. It is inevitable that it is what happens to Rachel that forces Lorenzo back to crime - the only thing that's not inevitable is whether his slip is an one-off or permanent.

Pelecanos is best known in the UK for his collaboration with David Simon on The Wire and Treme. What Pelecanos brought to the table was his fluency in 'street'. He conjures the speech of African American gang-bangers pitch-perfectly. His characters are deftly drawn and they carry the plot with an easy, streetwise lope. Pelecanos is an absolute master of his genre. You either like it or you don't. Personally, I love it.

Wednesday, 2 May 2018

Prayer - Philip Kerr

Philip Kerr died, too young, a month ago. He is best known for his exemplary Bernie Gunther novels, several of which have been reviewed on this blog. I had only read one of his non-Gunther novels, the unimpressive sci fi Gridiron (1995). Prayer (2013) is very different. It is, I suppose, a splice of supernatural suspense and a police procedural. Giles Martins, originally from Scotland, is now with the FBI in Houston, Texas. His marriage to Ruth is on the rocks because 'Gil' has lost his faith in God. Meanwhile more famous sceptics - authors of anti-theistic books - are dying in very unusual, even terrifying circumstances. Because this might be some form of domestic terrorism, Gil is assigned to investigate.

I don't really want to go any further with the synopsis because Kerr's novels are so brilliantly plotted there is always the danger of giving too much away. I very much like the typical Kerr twist - just as Bernie Gunther is the oxymoronic 'Good Nazi', so Prayer is fundamentally the testing of Gil's lack of faith. As such it works very well. You either roll with the premise or you don't. My lack of belief is as solid as these things get yet I was happy enough with the stages of Gil's purification. Kerr has always had a gift for characterisation and is almost as good with women characters as he naturally is with men. Ruth, the Christian wife, is a bit of a pain but Sara Espinosa, Gil's romantic interest, and especially the enigmatic Gaynor Allitt are strong enough to carry novels of their own.

Kerr has always been at home with first-person narration. Prayer is no exception. That said, I was less comfortable with the various chunks of reported prose, written by others, the style of which seemed always the same. I did not take to the villain and I find thrillers always work better if the villain is as charismatic on the page as he or she is said to be in the action.

Not Kerr's best book, then - he came out of the gates with his best material, the so-called Berlin Noir sequence - but well worth reading for its own sake. I might try and get hold Hitler's Peace next, a non-Gunther Nazi novel.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)