Total Pageviews

Saturday, 30 March 2019

Jack the Ripper - Daniel Farson

Farson's 1972 book introduced the barrister Montague Druitt as Number One Suspect. Actually - as is so often the case with this fascinating work - he put the name to the suspect that Leonard Matters had known about and dismissed in the first ever Ripper book (1928). Farson claimed to have seen the famous Macnaghten Memorandum, a note written by the man who took over as head of the Met immediately after the murders ceased. Farson would have us believe that Macnaghten wrote in his official capacity, a summary document to close the file. Actually what Macnaghten did (and Matters proves beyond reasonable doubt) is copy out Major Arthur Griffiths' suspect list from his 1898 Mysteries of Police and Crime (Part 1). Griffiths had overseen prisons but had never served with the police. He did, however, have extensive police contacts and it may well have been that both Griffiths and Macnaghten got their information from the same source. Was that source authoritative? Probably not, given the insistence that police inquiries wound down after Druitt's body was fished from the Thames on December 31 1888, when in fact key frontline investigators believed the Ripper continued killing. Inspector Reid turned up at various prostitute murders well into 1889 and 1890, and Inspector Abberline was apparently convinced that George Chapman (caught and hanged 1903) was the Ripper.

Farson's book is frankly nowhere near as good as Matters' original. Farson never gives us sources we can check whereas Matters always does. Again, the fact is, Matters shows us, almost half a century earlier, how weak Farson's theory really is. Farson's suspect is a reasonable candidate, whereas Matters' nominee is well nigh ridiculous; on the other hand, Matters' research is thorough and documented whereas Farson in the end resorts to absurd assertions. Farson also claimed (I haven't yet checked if the claim is true) that he is the first to produce a photograph of Druitt. He then goes on to shoot himself in the foot. Is that a glint of madness in the eye, he asks. Answer: no it isn't. Is that an incipient moustache? Absolutely not.

Actually, Farson's research, such as it is, was done for a pair of TV documentaries aired over a decade before the book came out (Farson was an early star of ITV). While the programmes were still be edited, the research dossier mysteriously disappeared, which raises rather obvious suspicions. Nevertheless the book was a big success (as the TV version had been) and really ushered in the great wave of Ripperology that persists to this day. It is essential and enjoyable reading. Farson has an engaging style - but I wouldn't trust him as far as I could throw him.

Thursday, 28 March 2019

The War Hound and the World's Pain - Michael Moorcock

The War Hound and the World's Pain (1981) is, I believe, the first of the von Bek series. I say 'believe' because Moorcock continues to revise and rebundle his back catalogue. There is definitely a walloping Von Bek single volume - I have seen it - and some apparent authorities mention a trilogy, though the complete Von Bek seems more than three times the size of this instalment. I therefore decided to go with the series as originally written and published.

I was surprised to find Ulrich von Bek starting out as a mercenary in the Thirty Years War 1618-48. The war was always silly U and went on far too long. Ulrich has certainly had enough, so he abandons his troop and rides off into the wilds of Germany. He finds himself in a forest. He realises that there is no bird song, no stirring of animals in the undergrowth. He finds a palatial castle - stocked with food but utterly uninhabited. Von Bek helps himself. The beautiful Sabrina arrives. He helps himself there, too. After some weeks of this Sabrina introduces him to the castle's owner, the fallen angel Lucifer. Lucifer, it turns out, has also had enough - enough of trying to keep the peace between the dukes of Hell, enough of being at odds with God who once loved him. Lucifer makes a pact with Ulrich. If Ulrich can recover the holy grail, which Lucifer can offer to God as a peace offering, then Ulrich can have his soul back and Sabrina.

Thus the quest begins... taking Ulrich and his companion Grigory Sedenko to the World's End, which mostly turns out to be an alternative world called Mittelmarch which co-exists within and alongside the real world. He fights various hellish enemies, mostly controlled by Johannes Klosterheim, former employer of the boy Sedenko, who is on a similar quest. Von Bek is assisted, from time to time, by Philander Groot, the dandy-magus, an echo of the sort of hero Moorcroft was developing in his rococo period ten years earlier.

The characters here are all well written. I especially enjoyed the angelic Lucifer and, of course, Groot. The story was compelling; at this stage of his career Moorcroft had the gift of writing exactly the amount his concept could bear. Whilst we know the story will continue, which it does in The City in the Autumn Stars, the quest here is self-contained - a good job given that the second instalment didn't arrive until 1986 which, given Moorcock's breathtaking productivity, must have seemed an age to keen readers.

Friday, 22 March 2019

The Ashes of Berlin - Luke McCallin

The Ashes of Berlin is the third of McCallin's Gregor Reinhardt novels. I reviewed the first, The Man From Berlin, earlier this year.

The date is 1947 and Reinhardt, a veteran of both World Wars, has returned to Berlin and his old job as a Police Inspector. The police department is chaos, filled with misfits and plants from each of the occupying powers. Reinhardt might be considered an American plant. He lives with the widow of his old mentor and shares his room with his former Kripo partner Rudi Brauer.

Reinhardt prefers the night shift when he is often alone. One night he is called to a double murder in the American sector. This launches him into an investigation of a serial killer. An officially illegal organisation for supporting former servicemen is involved. The victims all seem to have been associated with an off-the-books wartime operation in North Africa.

By about halfway through it has become clear who is responsible. Reinhardt himself has met the killer but he hasn't managed to see his face. Finding him and thus stopping him becomes the final challenge.

The book is excellently written and I had never a moment's doubt as to the astonishing depth of research on show. For this sort of story, in this setting, I wouldn't know where to begin. The final revelation, though, was a disappointment. Yes, McCallin had planted the clues from the beginning, but the killer's backstory just wasn't convincing for me. This sometimes happens. It by no means puts me off trying the volume I missed (The Pale House) or picking up the next Reinhardt when it comes.

The date is 1947 and Reinhardt, a veteran of both World Wars, has returned to Berlin and his old job as a Police Inspector. The police department is chaos, filled with misfits and plants from each of the occupying powers. Reinhardt might be considered an American plant. He lives with the widow of his old mentor and shares his room with his former Kripo partner Rudi Brauer.

Reinhardt prefers the night shift when he is often alone. One night he is called to a double murder in the American sector. This launches him into an investigation of a serial killer. An officially illegal organisation for supporting former servicemen is involved. The victims all seem to have been associated with an off-the-books wartime operation in North Africa.

By about halfway through it has become clear who is responsible. Reinhardt himself has met the killer but he hasn't managed to see his face. Finding him and thus stopping him becomes the final challenge.

The book is excellently written and I had never a moment's doubt as to the astonishing depth of research on show. For this sort of story, in this setting, I wouldn't know where to begin. The final revelation, though, was a disappointment. Yes, McCallin had planted the clues from the beginning, but the killer's backstory just wasn't convincing for me. This sometimes happens. It by no means puts me off trying the volume I missed (The Pale House) or picking up the next Reinhardt when it comes.

Friday, 15 March 2019

The Three-Body Problem - Cixin Liu

The Three-Body Problem is the first part of the trilogy Remembrance of Earth's Past.

It would be simplistic to compare Cixin Liu to Haruki Murakami, especially as both have written novels with similar-looking titles - China 2185 and 1Q84 respectively. But in truth there are very few similarities other than the fact that we in the West are extremely ignorant of contemporary trends in oriental literature.

Hurakami is a fantasy writer who dabbles in science fiction. Liu is hard-wired sci fi. There is a touch of fantasy in this novel but only as a literary device to introduce the male protagonist to the core idea of the book. Wang Miao is a researcher in nanomaterials, so you get an idea of just how extreme the central premise is. He is introduced to a VR game called Three Body. In the game historical scientists - some so ancient as to be mythical - try to solve the problem of an unstable world which crashes from civilisation to apocalypse and back again. Only the most knowledgeable and persistent players work out the answer and when they do they are invited to share a secret - that the world of the game is real and that the inhabitants of that world have been in touch.

The female protagonist Ye Wenjie watched her astrophysicist father get stoned to death during the Cultural Revolution in 1967. An astrophysicist herself, she is taken to a rural outpost for 're-education'. She starts at the bottom of the hierarchy, working with the basic mechanics of the radio scanner. But she progresses. The work becomes her obsession and she abandons hope of ever re-joining civil society. Eventually she is sufficiently trusted to be allowed into the secret of the real purpose of the scanner - the search for extra-terrestrial life - and she is on duty when the first message comes through.

After twenty years or more, China has changed. It has opened up, to a certain extent, to the West. Ye Wenjie is restored to academia. She develops followers, with whom she creates the Three Body game. She ends up, in the 'present' of the novel, which is a few years in the future, as the secret high priestess of the cult awaiting the arrival of the extra-terrestrials. Other secretive factions, including international security services, are not so keen.

Whilst it is not an easy read, especially for the science-phobic like me, The Three-Body Problem is nevertheless an extraordinary achievement. Cixin Lui is a scientist and obviously knows his stuff. He is equally in command of literary devices: the meta-drama of the game, the seamless sliding through time, even a spot of noir crime. I genuinely have never read a book like this. I simply have to read the next in the trilogy, The Dark Forest.

Sunday, 10 March 2019

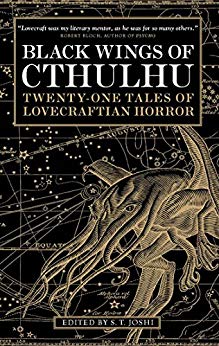

Black Wings of Cthulu (1) - S T Joshi (ed)

It's a measure of the influence of H P Lovecraft that so many others have written in homage. This is a substantial collection of 21 stories of varying length and Joshi has gone on to edit nine more to date - and these, of course, are just in reference to the Lovecraft's Cthulu or Elder Gods stories. He wrote plenty more that are more straightforwardly Gothic.

There are no bad stories here. I can only therefore mention my favourites. Caitlin R Kiernan's "Pickman's Other Model" gets the collection off to a flying start. I liked Sam Gafford's "Passing Spirits" and I loved "Inhabitants of Wraithwood" by W H Pugmire, which also develops Lovecraft's story "Pickford's Model", as does Brain Stableford in "The Truth About Pickman".I tend to prefer the longer stories but the one here that stayed in my mind the longest was "Susie" by Jason van Hollander, which closes the collection and only lasts seven pages - seven pages into which he crams several brilliant twists. Van Hollander also did the cover illustration which perfectly captures the theme.

There are no bad stories here. I can only therefore mention my favourites. Caitlin R Kiernan's "Pickman's Other Model" gets the collection off to a flying start. I liked Sam Gafford's "Passing Spirits" and I loved "Inhabitants of Wraithwood" by W H Pugmire, which also develops Lovecraft's story "Pickford's Model", as does Brain Stableford in "The Truth About Pickman".I tend to prefer the longer stories but the one here that stayed in my mind the longest was "Susie" by Jason van Hollander, which closes the collection and only lasts seven pages - seven pages into which he crams several brilliant twists. Van Hollander also did the cover illustration which perfectly captures the theme.

Tuesday, 5 March 2019

Majic Man - Max Allan Collins

Majic Man (1999) is the tenth of Collins's Nate Heller series. If you think that's a lot, you seriously underestimate Max Allan Collins. A glance at the list on his website will soon put you right. For someone who has written so much, I am amazed at the standard Collins consistently achieves. Majic Man is no exception.

The thing with Heller is that he has been involved in every American major crime/unsolved mystery in the second half of the 20th century. Now, in retirement, he is committing his secrets to paper.

The stories are therefore based on fact. The fact comes from a reasonable amount of research - and Collins names his sources in quite a useful literature review at the back.

The year is 1949 and PI Nate is hired by James Forrestal, President Truman's Defense Secretary because he believes someone is out to get him. Certainly the powers-that-be are on his case. Very soon he is forced out of office on health grounds and confined to the psychiatric unit at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland. Is this because he was a keen financier of Hitler before the war - or because of something he knows from his time in government? And by the way, this much is all historical - that's Forrestal's photo on the cover.

The cover also gives away the second string of the novel. Is the Roswell Incident, the 'UFO' crash and possible military capture of a surviving alien, what Forrestal knew about? Nate heads for New Mexico to investigate. Nate and presumably his author - reach fascinating conclusions. The entire novel is fascinating thanks to the way Collins combines history and (disputed) fact with all the tropes of postwar noir crime fiction.

I really enjoyed Quarry's Choice last year and I loved Majic Man. Fortunately there are heaps of Collins's mammoth oeuvre still to tackle.

Friday, 1 March 2019

The Disappeared - C J Box

The blurb claims Box is "The #1 American Crime Writer". Well, he's not that. Better claims can be made for various others. I suspect most would have Ellroy on their list and of those, I would suggest that Don Winslow rides pretty high in their estimation. That said, Box is a prolific and very successful author who pursues a very American line of crime fiction - rural backwoods, nothing too violent, investigated by a local with a deep family background and impeccable morals.

In this case the backwoods are Wyoming, the investigator Joe Pickett, a game warden who has previously worked as the agent of the state governor. Now there is a new, very different governor but he still wants Joe to probe the disappearance of a British woman entrepreneur from a holiday ranch where it just so happens Joe's eldest daughter works. It also happens that the local game warden has vanished, which gives Joe a reason to provide temporary cover.

The Disappeared is my first Box novel and I liked it. I normally prefer my crime fiction several shades darker and bloodier, but Box is a highly skilled writer who does deep research. His flair for the locale sucks you in and it doesn't matter one jot if you haven't read any of the other 17 Pickett novels; Box provides just enough exposition without you even noticing. I especially liked Joe's friend Nate Romanowski, a loose cannon professional falconer. I like any character who can weaponise a trout. The plot is clever, the subplots subtly interwoven. I will definitely be reading more Box.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)