Total Pageviews

Monday, 30 April 2018

Mary Ann in Autumn - Armistead Maupin

Mary Ann in Autumn is the eighth instalment of Maupin's magnificent Tales of the City, but only the second novel. The first was effectively a collection of his newspaper column and the next five stuck to that format. Then came Michael Tolliver Lives (2007), the first novel, which is also reviewed on this blog. Then comes Mary Ann in Autumn. The good/bad news is that there is a third novel, The Days of Anna Madrigal (2014) which we have to presume is the end.

The best news, though, is that Mary Ann is as good as anything earlier in the series, which means it is superlatively good. Maupin's great gift is that he tackles all the daily problems of San Francisco's gay and trans communities over a period of forty-plus years and he does it with love, compassion and a deep understanding of the human condition. A lesser artist would make it all about sex, perhaps with some exploration of the consequences of coming out. Maupin's characters are already out when we first meet them. We can take their sexual orientation or body dysmorphia as read.

Mary Ann, the great prude of 1978, returns to San Francisco having seen her husband and her life coach enjoying oral sex via Skype. The timing could have been better - she's also just found she has ovarian cancer. In coming to terms with the possibility of death, she in fact comes to terms with the endless possibilities of life. She is hosted by Michael and his husband Ben, supported by Dee Dee and her wife D'or, and inspired by the increasingly frail Anna Madrigal. Anna is now living with Michael's assistant Jake, who is transitioning to male. There is much awkwardness when he meets a Mormon Missionary who has gay leanings. There is also a secondary storyline involving Mary Ann's estranged daughter Shawna and a gangrenous beggar who turns out to have links to Mary Ann herself.

It is all brilliantly and (on the face of it) effortlessly done. The effortlessness is only skin deep. Maupin has spent a lifetime exploring these much-loved characters. He knows their every tic, hang-up and memory. He takes the same amount of care with characters who only appear (or reappear) in this novel. Even the worst of them has a soul and even the dogs have characters.

Superb.

Wednesday, 25 April 2018

Blackshirt: Sir Oswald Mosley and British Fascism - Stephen Dorril

Dorril has given us an exhaustive, not to say exhausting, slab of a book about the Brit who would have been Hitler. The research is thorough and everything Dorril discovered is here. Two problems: (1) he doesn't like Sir Oz, which is by no means a sin but doesn't augur well for a biographer; and (2) he isn't really interested in fascism per se.

Regarding the not-at-all great man, Dorril has a thesis that he was a narcissist. No, really? A politician who considers himself the greatest thing since sliced bread? An aristo who is a wee bit arrogant? Surely not! Some numpty in the quotes on the back describes Mosley as a brilliant politician. No he wasn't. He bought himself a Labour seat and never won another election. He might have been a powerful orator but he was a hopeless politician.

Not discussing pre-BUF fascism undermines Dorril's story because it is important to realise how fashionable fascism was in the 1920s. The fascists were everywhere. When he left Labour and invested a job lot of black shirts, Mosley wasn't heading out into the political wilderness, he was jumping on the bandwagon of his day.

It's a decent book but there are better ones around. The best book about Mosley is written by his son, and as for British fascism, just look at Dorril's sources. My own favourite is Hurrah for the Blackshirts because we can't remind the great British public too often about the Daily Mail and Hitler. In fairness, Lord Rothermere wasn't anything like as keen on Mosley. He regarded him as jumped-up opportunist prat, which is a pretty good assessment. Mosley isn't the story of British fascism, he's the reason it didn't succeed.

Friday, 20 April 2018

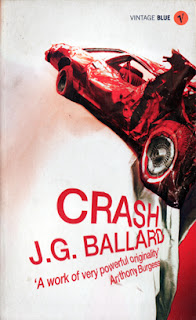

Crash - J G Ballard

Ballard's fiction sprouted from ideas, not character. His characters tend to by cyphers, even when - as here - they are actually called James or Jim Ballard. The idea here, in 1973, is that cars have become fetishes, the greatest fetishes ever because we build endless motorways and parking facilities to accommodate them.

James has an accident and while in hospital he becomes peripherally aware of Vaughan, a former TV star who lost his career when he lost his looks in a crash of his own. Vaughan has become something of an iconoclast. The only way he can get sexual arousal from the car-fetish is by crashing. He has devised elaborate sexual fantasies about the death-by-car of the film star Liz Taylor, who is in Shepperton, the ultimate Ballard location, filming some rubbish of the kind that propped up the British film industry in the 1970s.

James has a modern marriage. He and his wife are both besotted with Vaughan and his scars. James goes further and has complicated sex with Gabrielle, who has been crippled in her accident, in her specially adapted invalid car.

The book is profoundly offensive and is meant to be. After a while you come - as intended - to view the car-sex in the same way you might skim through a list of the latest features on the car you were always going to buy anyway. For most of the book Ballard uses exactly the same language - blunt, functional, technical - for sexual orifices that he uses for buttons and switches on the cars. Things liven up when Vaughan and Ballard have wild sex on acid outside a breaker's yard.

Crash is a technical exercise rather than a novel. It achieves its purpose and I'm glad I read it. I won't be reading it again.

James has an accident and while in hospital he becomes peripherally aware of Vaughan, a former TV star who lost his career when he lost his looks in a crash of his own. Vaughan has become something of an iconoclast. The only way he can get sexual arousal from the car-fetish is by crashing. He has devised elaborate sexual fantasies about the death-by-car of the film star Liz Taylor, who is in Shepperton, the ultimate Ballard location, filming some rubbish of the kind that propped up the British film industry in the 1970s.

James has a modern marriage. He and his wife are both besotted with Vaughan and his scars. James goes further and has complicated sex with Gabrielle, who has been crippled in her accident, in her specially adapted invalid car.

The book is profoundly offensive and is meant to be. After a while you come - as intended - to view the car-sex in the same way you might skim through a list of the latest features on the car you were always going to buy anyway. For most of the book Ballard uses exactly the same language - blunt, functional, technical - for sexual orifices that he uses for buttons and switches on the cars. Things liven up when Vaughan and Ballard have wild sex on acid outside a breaker's yard.

Crash is a technical exercise rather than a novel. It achieves its purpose and I'm glad I read it. I won't be reading it again.

Labels:

car-sex,

Crash,

dystopia,

Elizabeth Taylor,

fetish,

j g ballard,

sci fi,

Vaughan

Wednesday, 18 April 2018

A Book of American Martyrs - Joyce Carol Oates

I don't know how she does it. Joyce Carol Oates has been writing novels for 54 years. To all intents and purposes she publishes one a year. Not only does she show no sign of flagging, she just gets better and better.

This, despite its terrible title (a play, I think, on Foxe's Book of Martyrs) stretches for over 700 pages and something like thirteen years. Essentially, extreme Christian Luther Amos Dunphy becomes convinced that God wants him to murder the doctors who murder babies in the womb - abortionists, operating perfectly legally in state funded women's clinics. His victim is Gus Vorhees. In November 1999 Dunphy shoots him down, kills him, and calmly surrenders to the authorities. The only problem is, he also shoots and kills the volunteer who drove Vorhees to work, a Vietnam veteran.

Dunphy refuses to plead in court and will only accept the court-appointed public defender, despite the thousands of dollars raised by rightwing evangelicals. Nevertheless, a jury in his hometown of Muskagee Falls, Ohio, fails to convict. Dunphy remains in gaol until a second trial finds him guilty. This being Ohio, he receives a death sentence. No one expects him to be executed. The two families - that of assassin and victim - enter that uniquely American martyrdom of waiting for justice to take its course.

The families are very different in terms of class, education and beliefs. In other respects they are not so different. A mother left with a handful of young children. Neither mother is functioning. Edna Mae Dunphy is lost in religious delirium. Her older children, Lucas and Dawn, have to assume responsibility. Lucas ducks out as soon as he is old enough to leave school. Dawn does her best to do her duty but other kids in her new hometown - the wonderfully named Mad Junction - bully and attack her. Dawn is a big girl. She fights back and...

Meanwhile, Jenna Vorhees, a lawyer, effectively abandons her three children to go on a crusade defending women's right to choose. Her daughter Naomi begins putting together an archive of her father's life and death. Eventually that leads her to her grandmother and her uncle, both splendid New York elite eccentrics. It also leads, finally, to Dawn Dunphy, now a professional female boxer awaiting her title shot.

We have marvelled throughout at Oates's literary skill - the different prose styles she uses for the two families, the italicised quotes which we eventually realise are from Naomi's archive. But then, in the final quarter, Oates reveals her particular talent, which those not in the know would never expect of a New England grande dame professor of a certain age. The fact is, Joyce Carol Oates is one of the world's great boxing writers. In my opinion her only rival is Norman Mailer. And Mailer, so far as I know, never wrote anything as good as the last two chapters of An American Book of Martyrs. Frankly, it's essential reading.

This, despite its terrible title (a play, I think, on Foxe's Book of Martyrs) stretches for over 700 pages and something like thirteen years. Essentially, extreme Christian Luther Amos Dunphy becomes convinced that God wants him to murder the doctors who murder babies in the womb - abortionists, operating perfectly legally in state funded women's clinics. His victim is Gus Vorhees. In November 1999 Dunphy shoots him down, kills him, and calmly surrenders to the authorities. The only problem is, he also shoots and kills the volunteer who drove Vorhees to work, a Vietnam veteran.

Dunphy refuses to plead in court and will only accept the court-appointed public defender, despite the thousands of dollars raised by rightwing evangelicals. Nevertheless, a jury in his hometown of Muskagee Falls, Ohio, fails to convict. Dunphy remains in gaol until a second trial finds him guilty. This being Ohio, he receives a death sentence. No one expects him to be executed. The two families - that of assassin and victim - enter that uniquely American martyrdom of waiting for justice to take its course.

The families are very different in terms of class, education and beliefs. In other respects they are not so different. A mother left with a handful of young children. Neither mother is functioning. Edna Mae Dunphy is lost in religious delirium. Her older children, Lucas and Dawn, have to assume responsibility. Lucas ducks out as soon as he is old enough to leave school. Dawn does her best to do her duty but other kids in her new hometown - the wonderfully named Mad Junction - bully and attack her. Dawn is a big girl. She fights back and...

Meanwhile, Jenna Vorhees, a lawyer, effectively abandons her three children to go on a crusade defending women's right to choose. Her daughter Naomi begins putting together an archive of her father's life and death. Eventually that leads her to her grandmother and her uncle, both splendid New York elite eccentrics. It also leads, finally, to Dawn Dunphy, now a professional female boxer awaiting her title shot.

We have marvelled throughout at Oates's literary skill - the different prose styles she uses for the two families, the italicised quotes which we eventually realise are from Naomi's archive. But then, in the final quarter, Oates reveals her particular talent, which those not in the know would never expect of a New England grande dame professor of a certain age. The fact is, Joyce Carol Oates is one of the world's great boxing writers. In my opinion her only rival is Norman Mailer. And Mailer, so far as I know, never wrote anything as good as the last two chapters of An American Book of Martyrs. Frankly, it's essential reading.

Tuesday, 10 April 2018

The Harder They Come - T C Boyle

Boyle's more recent work seems to have settled into a sort of skewed state of the nation groove. When the Killing's Done was broadly about environmentalism, The Harder They Come is generally about survivalism. I use the word skewed because we are talking Boyle here, author of The Road to Wellville (enough fibre in your diet will quell your baser instincts) and, my personal favourite, Riven Rock. Boyle might start out in contemporary America but you are always going to end up somewhere in the past. Here, it is the closing years of the 18th Century and our avatar is the legendary mountain man John Colter.

Adam Stenson likes to be called Colter, in homage to his hero. When he is off his meds Adam starts thinking he is Colter, which makes everyone else he comes across 'hostiles'. Adam's dad, Sten, is a recently retired high school head who has become a local hero after tackling and killing an armed Costa Rican robber on his post-retirement cruise. Not that Sten is by nature a have-a-go-hero but the old Vietnam training never really goes away.

Adam has been living quite happily in the woods at his maternal grandmother's house, merrily developing a poppy plantation and milking the seed-heads. But the old lady is dead now and Adam's parents want to sell the house to cover the costs of their move to the Californian seaside. Adam resents this deeply, albeit he's built himself a couple of bunkers in the woods. Then he meets Sara, a militant freethinker twice his age - and things start to go generally haywire.

Boyle is a genius writer with a gift for taking you inside the heads of his various characters. Storylines overlap and intersect so smoothly you can't quite see the joins. His characters are always fundamentally decent people who have inadvertently found themselves adrift from mainstream life. I have devoured his novels ever since I first picked up Drop City ten or so years ago. I love his attitude almost as much as I love his writing. I recommend him without reservation.

Thursday, 5 April 2018

The Force - Don Winslow

Been waiting months for this, Winslow's latest, soon to be a major TV series, to come out in paperback. The moment I hear it's in the shops I'm off to Waterstones to snap up my copy. Started reading it that same night.

For anyone who saw The Shield or read Joe Wambaugh's Choirboys back in the Seventies, there's nothing new here. In fact, the situation is slightly worse than that. The storyline in The Force is virtually identical to that of The Shield. The behaviour of the NYPD is no worse in 2017 than it was in the Wambaugh more than forty years earlier. Indeed, Wambaugh's cops were better drawn and I cared more about their fate.

For those, like me, who have read Winslow's Power of the Dog, The Cartel and - best of all - Savages, The Force comes as a massive let down. In those earlier novels Winslow had staked out a territory all his own, with multiple intersecting storylines and deep background. This is New York, ground well and truly trodden, and reads more like a TV novelisation than original fiction. In fact, were Winslow an unknown, I doubt it would ever get accepted for TV because the male anti-hero is a walking-talking stereotype and there is no strong woman to counter him. This latter point is a criminal shame because the other Winslow books I mentioned are packed with interesting women.

It is not badly written - Winslow couldn't write badly if he tried - but compare it with Savages, where even the layout of the words on the page fizzes with invention, and it's pretty stodgy stuff. I liked the character of Monty and I liked Malone's snitch Nasty Ass. Other than that I didn't give two hoots about any of them, especially Malone which, when you've spent 480 pages seeing the world entirely from his point of view, is a frankly damning indictment.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)