Total Pageviews

Wednesday, 27 November 2019

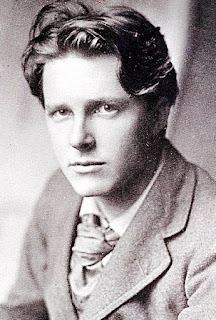

Rupert Brooke, Life, Death and Myth - Nigel Jones

Jones's book, first published in 1999 and revised for this Head of Zeus edition in 1915, is the most up-to-date study of the poet. Like Lehmann (reviewed below) it has the advantage of being written after all the guardians of the flame (the Brooke Trustees) had died and relinquished their stranglehold, but Jones rather tarnishes the freedom by making Brooke as unpleasant as possible. Some of Brooke's behaviour, particularly to women, is shameful - but I wonder, weren't we all like that when we were young and naive? Brooke was only 27 when he died, which admittedly is not all that young, but he was still financially reliant on his mother and surrounded by friends, would-be lovers and general sycophants who surely retarded the development of his character. Having now studied dozens of books on him in the last three months, I am of the opinion that Brooke only approached man's estate after his last tour to America and Canada and the South Seas in 1913-14. His behaviour seemed to moderate (Maurice Browne's 1927 Recollections are helpful in this, as he only met Brooke in 1914) and people started to see him as a man rather than a gilded youth. Certainly his poems mature considerably between Georgian Poetry (1911) and the war Sonnets (1914).

Jones's book is also absurdly long at 564 pages. You simply cannot justify that level of wordage for a man who died at 27. Equally, there are only so many times you can criticise the stifling hand of his patron Eddie Marsh and the Trustees under his lifelong friend Geoffrey Keynes. Both these men were successful and important in their own right. They believed - genuinely - they were acting in Brooke's best interests at the time and, given that neither disposed of the less flattering material, I believe it is reasonable to suppose that they realised attitudes would change in later years. Keynes was still alive when Michael Hastings produced his iconoclastic work, The Handsomest Young Man in England in 1967, and nobody tells Hastings what to write.

In summary, everything you could possibly want to know about Rupert Brooke is here in Jones. You might want to moderate Jones's rather black and white judgments a little with Lehmann and a look at Hastings (essentially a picture-book interspersed with very interesting commentary). If you can find a copy (it was privately printed) Browne is a startling insight into the modernist world that Brooke also enjoyed. Chicago is, after all, a long way from Grandchester.

Tuesday, 26 November 2019

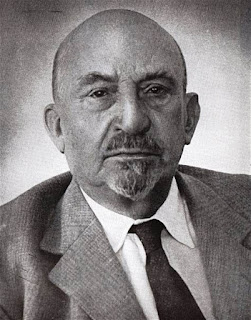

The Sun Chemist - Lionel Davidson

How on earth do you make a thriller out of writing footnotes for the letters of Israel's first president? Lionel Davidson shows how. Igor Druyanov, a historian of Russian descent, is commissioned to prepare a couple of installments of the massive multi-volume Letters of Chaim Weizmann (1874-1952). The years in question were Weizmann's wilderness years - like Churchill, these were the Twenties and Thirties - when he was ousted from the Zionist movement and had to revert to his original profession as a research chemist.

The key to the tension here is that the book dates from 1976 and begins a couple of years earlier, in 1974. This is when OPEC jacked up oil prices, creating a crisis in the West and making the polite, ever-smiling Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani a hate figure. At rhe time it seemed as if the greedy, ungrateful Arabs were threatening the developed world with a new stone age. Indeed, the West has spent the last fifty years developing alternative power sources to avoid a repeat, whilst the Arab world has taken a more moderate line in exploiting what is, after all, their only real resource, and a finite one at that.

But Davidson's book is firmly anchored in 1974-6 and the Israel of that time, a year or so after the first Arab-Israeli war. Davidson might have been born in Hull but at this time he was living in Israel. In the story, it emerges from Igor's research that Weizmann and his research associates might have hit upon a way of synthesizing combustible fuel from root vegetables. It isn't quite so simple, and Davidson spares us none of the science, but that is essentially it: an infinite supply of fuel to a power-hungry world; a windfall beyond price to a state just establishing itself in the deserts of Palestine and the end of time to their near neighbours in the Gulf.

It's a great book and an astonishing feat of writing from Davidson. He was never a scientist, always a journalist but, by God, he does his research. Every part of the book, from the history that drives Druyanov, to the world of international science and petrochemicals, is utterly convincing. Davidson, to be fair, was a peripatetic journalist and, as I say above, lived in Israel - but I've never read anything, fact or fiction, that brings that raw state so alive. Davidson, in my view, is even better than Ambler, better than Greene, and so unusual in his choice of subjects. He deserves to be better remembered than he is. As for this book, is there a thriller in print today that is more topical?

Sunday, 17 November 2019

The Silence of the Girls - Pat Barker

I was a big fan of the Regeneration Trilogy, not quite so keen on the Life Class Trilogy, although I still enjoyed it. Neither prepared me for this. The Silence of the Girls is a masterpiece - it's as simple as that. Barker takes the exact same episode of the Trojan War that Homer does, the 'wrath of Achilles', and does it from the woman's point of view. Given that Agamemnon's depriving Achilles of his prize slave Briseis, the captured queen of Trojan Lyrnessus, prompted the long sulk, this is an even better concept than Homer's. We see everything from all sides, Greek, Trojan, man, woman. And the change that Briseis brings about in Achilles, after the death of Patrocolus, is beautifully done by Barker and utterly convincing. I also loved the way she depicted the hero's eerie mother, the sea-nymph Thetis. That said, all her characterisations worked for me: the aged Priam, the simple Ajax, the individual enslaved women, and best of all, ever-patient Patrocolus. There is nothing more I can say. The best book I have read this year. A true work of art. I relished every single word.

Thursday, 14 November 2019

A Wrinkle in the Skin - John Christopher

A Wrinkle in the Skin, A Terrible Title, is a 1965 disaster novel by John Christopher (Sam Youd), creator of the Tripods and author of the classic The Death of Grass.

Christopher has enjoyed something of a revival since his death in 2012. He is regarded as a prophet of ecological disasrer, which is certainly the case with The Death of Grass and The World in Winter. A Wrinkle in the Skin is certainly global but the disaster is not man-made. Vast earthquakes have reshaped the Earth, to the extent that the English Channel has dried up. The tidal wave that accompanied the quakes has wiped away coastal cities like Southampton and Bournemouth.

Our hero, Matthew Cotter, grows tomatoes on Guernsey. The quake makes a mess of his glasshouses but he is unscathed. He wanders about the island and finds others who have survived. They are very few, but they group together, find food and start to make a sort of life. Matthew, however, is determined to find his daughter Jane who he knows spent the night of the apocalypse in East Sussex. So he sets out to walk there, there being no deep water to stop him., accompanied by the orphaned boy Billy.

This is unfortunate - mature man and immature child on a mission of discovery has become a cliche of post-apocalyptic fiction (The Road, for example). To be fair, Christopher wrote in 1965 and I'm pretty sure it wasn't a cliche back then. So they meet a mad king (actually a sailor, the solitary survivor on an oil tanker stranded on the dry bottom of the Channel, desperately trying to keep everything literally shipshape. They meet a Preacher, a visionary of the apocalypse who foresees the Risen Christ approaching from the East. And they meet other groups, good and bad and extremely bad. It's all a bit predictable - except that I liked the ambition of making the ship a supertanker, I liked that the religious crazy was a hospitable host, and I really liked April, the sole female character who is fully characterised. There is a conversation between April and Cotter which is both shocking and moving - which inspires Matthew to pursue his quest to the bitter end (another excellent twist) and the scales to finally fall from his eyes.

A good book, then, not as significant as some of Christopher's others but effective and skillfully done.

Christopher has enjoyed something of a revival since his death in 2012. He is regarded as a prophet of ecological disasrer, which is certainly the case with The Death of Grass and The World in Winter. A Wrinkle in the Skin is certainly global but the disaster is not man-made. Vast earthquakes have reshaped the Earth, to the extent that the English Channel has dried up. The tidal wave that accompanied the quakes has wiped away coastal cities like Southampton and Bournemouth.

Our hero, Matthew Cotter, grows tomatoes on Guernsey. The quake makes a mess of his glasshouses but he is unscathed. He wanders about the island and finds others who have survived. They are very few, but they group together, find food and start to make a sort of life. Matthew, however, is determined to find his daughter Jane who he knows spent the night of the apocalypse in East Sussex. So he sets out to walk there, there being no deep water to stop him., accompanied by the orphaned boy Billy.

This is unfortunate - mature man and immature child on a mission of discovery has become a cliche of post-apocalyptic fiction (The Road, for example). To be fair, Christopher wrote in 1965 and I'm pretty sure it wasn't a cliche back then. So they meet a mad king (actually a sailor, the solitary survivor on an oil tanker stranded on the dry bottom of the Channel, desperately trying to keep everything literally shipshape. They meet a Preacher, a visionary of the apocalypse who foresees the Risen Christ approaching from the East. And they meet other groups, good and bad and extremely bad. It's all a bit predictable - except that I liked the ambition of making the ship a supertanker, I liked that the religious crazy was a hospitable host, and I really liked April, the sole female character who is fully characterised. There is a conversation between April and Cotter which is both shocking and moving - which inspires Matthew to pursue his quest to the bitter end (another excellent twist) and the scales to finally fall from his eyes.

A good book, then, not as significant as some of Christopher's others but effective and skillfully done.

Monday, 11 November 2019

Rupert Brooke, His Life and Legend - John Lehmann

I have been reading a lot about Rupert Brooke lately, in connection with a couple of personal projects of which, hopefully, more later. There are a fair few works on Brooke but the vast majority suffer from an obvious problem - length. Brooke was astonishingly busy, he wrote a lot from an early age, he had an enormous social circle and he travelled the world. But even so, he was only 27 when he died, and you simply can't justify 500+ pages for a life that short.

John Lehmann (1907-87) came of an astonishingly intellectual and creative family. His sister Rosamund was a novelist, his sister Beatrix a highly-celebrated actress. John was a poet and publisher. He founded New Writing in 1936, became a managing director of the Hogarth Press in 1938 and founded his own firm, John Lehmann Limited, in 1946. Finally, in 1954, he started The London Magazine. It's all very close-knit, a bit incestuous, and a bit artsy-craftsy. Which made him the perfect author for a critical biography of Rupert Brooke, who was a beneficiary and part-creator of similar arrangements before his ludicrous death in 1915. Best of all, Lehmann can do in 170 pages what Brooke's other biographers can't manage in several hundred pages. He brings Brooke alive in all his contradictory aspects - obsessed with women but offensively dismissive when the mood takes him; flirting with homosexuality but keeping his patron Eddie Marsh, who worshiped him, at a very resolute arm's length; globetrotting but always trying to micromanage his English friends. He was not a nice man but he was extraordinarily beautiful. He was a talented poet, more gifted than most in his day but did not live long enough to become truly great. And, as Lehmann says, he has been abandoned by the lirerary world which prostrated itself before his metaphorical shrine in 1915, in favour of those who came shortly after him and who lived long enough to experience the true horror of mechanized war: Sassoon, Owen and Graves.

Lehmann treats Brooke's service in a respectful and fair manner. Brooke was a volunteer, as everyone was in 1914. He did not ask Marsh, who was Churchill's secretary, to get him a safe billet in the Royal Navy Voluntary Reserve and it soon proved not to be particularly safe. Lehmann is better than most is describing Brooke's single experience of being under fire, in the long-forgotten farce of the British attempt to relieve the German siege of Antwerp. And let us not forget that Brooke was en route for the Dardanelles and the mass slaughter of Gallipoli when sunstroke did for him.

For anyone wanting to dip their toe into Brooke studies and come away with solid facts and a sound appraisal of his achievements, I cannot recommend Lehmann too highly.

John Lehmann (1907-87) came of an astonishingly intellectual and creative family. His sister Rosamund was a novelist, his sister Beatrix a highly-celebrated actress. John was a poet and publisher. He founded New Writing in 1936, became a managing director of the Hogarth Press in 1938 and founded his own firm, John Lehmann Limited, in 1946. Finally, in 1954, he started The London Magazine. It's all very close-knit, a bit incestuous, and a bit artsy-craftsy. Which made him the perfect author for a critical biography of Rupert Brooke, who was a beneficiary and part-creator of similar arrangements before his ludicrous death in 1915. Best of all, Lehmann can do in 170 pages what Brooke's other biographers can't manage in several hundred pages. He brings Brooke alive in all his contradictory aspects - obsessed with women but offensively dismissive when the mood takes him; flirting with homosexuality but keeping his patron Eddie Marsh, who worshiped him, at a very resolute arm's length; globetrotting but always trying to micromanage his English friends. He was not a nice man but he was extraordinarily beautiful. He was a talented poet, more gifted than most in his day but did not live long enough to become truly great. And, as Lehmann says, he has been abandoned by the lirerary world which prostrated itself before his metaphorical shrine in 1915, in favour of those who came shortly after him and who lived long enough to experience the true horror of mechanized war: Sassoon, Owen and Graves.

Lehmann treats Brooke's service in a respectful and fair manner. Brooke was a volunteer, as everyone was in 1914. He did not ask Marsh, who was Churchill's secretary, to get him a safe billet in the Royal Navy Voluntary Reserve and it soon proved not to be particularly safe. Lehmann is better than most is describing Brooke's single experience of being under fire, in the long-forgotten farce of the British attempt to relieve the German siege of Antwerp. And let us not forget that Brooke was en route for the Dardanelles and the mass slaughter of Gallipoli when sunstroke did for him.

For anyone wanting to dip their toe into Brooke studies and come away with solid facts and a sound appraisal of his achievements, I cannot recommend Lehmann too highly.

Monday, 4 November 2019

Acts of Allegiance - Peter Cunningham

I find myself conflicted over the modern Irish novel, of which this is certainly one. I hate the formulaic family-in-a-misty-soggy-paradise novel which has dominated the Booker for so long. On the other hand there are standout marvels like Roddy Doyle. Peter Cunningham, on the evidence of this novel, falls somewhere between the two.

There are heinous echoes of the formula - the roguish Pa who puts on a front, the matriarch's house which includes people who may or may not be family members. But against that we have the personal story of Marty Ransom who has bridged the border by collaborating with the Brits whilst building a career in the Irish diplomatic corps. And the compelling antagonist of Iggy Kane, Marty's cousin and childhood boon companion.

The balance between the two is not quite right. Cunningham essentially has three storylines going - childhood, young adulthood, and subsequent, ultimate betrayal. The one that doesn't get quite enough play, for me, is the betrayal. We perhaps need just one more example of Iggy's activities in the North before he blasts his way back into Marty's life. That said, the betrayal itself is beautifully done.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)