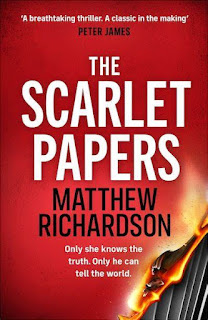

Apparently a debut spying novel, The Scarlet Papers is very impressive indeed. Matthew Richardson has tackled all the major tropes of the British genre and acquitted himself splendidly. Moles within the SIS, seedy postwar compromises, double agents, triples, illegals, even the real-life embodiment of super-evil, Mad Vlad.

Max Archer, failed MI6 applicant turned failed academic, is summoned to meet the legendary Scarlet King, first and only female C, active in the field from 1946 all the way to 1992. Now in her 90s, it seems she wants to publish her tell-all autobiography but needs Max, author of two failed books on Philby and other traitors, to fact-check it.

Obviously, a recipe for disaster. The powers-that-be can't have that sort of thing coming out. Some of Scarlet's secrets are big enough to bring down governments, let alone their creepy secret agencies. The chase is on and it's Max who finds himself on the front-line, with only a dual national private intelligence operative to help him.

Again, Richardson handles this remarkable well. The theme is preposterous, but then so are all actual spying scandals. Richardson has not only done his homework, fleshing out the narrative with historical parallels, but he brings it right up to date with the botched Skripol poisoning - one off-the-books op for Scarlet, post-retirement, is accompanying the swapped Skripol to the UK.

The best thing, though, is that the action is suitably thrilling. I enjoyed The Scarlet Papers hugely and will be searching the shelves for more by Mr Richardson.